"Is True Wisdom Built on Paradoxes?"

Wisdom can be defined as a set of fundamental truths that become more evident over time. Often, these truths are expressed in ways that seem self-contradictory at first glance. A paradox is something that seemingly contradicts itself, yet upon closer examination does not—the contradiction is only apparent. Throughout philosophy, religion, and history, we find that many profound insights take a paradoxical form. The idea that “all wisdom is paradox” suggests that the deepest truths often involve holding opposing ideas together. By exploring examples from diverse traditions, we can see how enduring wisdom frequently presents itself as paradox—statements that puzzle the mind initially but reveal deeper meaning with reflection.

Paradoxical Wisdom in Western Philosophy

Socrates’s "Knowing Nothing" Paradox

Western philosophers have long used paradox to convey insight. These paradoxes force us to question assumptions and look beyond surface logic to grasp a larger truth.

Socrates is famous for the statement “I know that I know nothing.” In Plato’s Apology, Socrates explains that he is wiser than those who think they know something because he at least recognizes his own ignorance. This seems contradictory—claiming to “know” one’s own lack of knowledge—but the paradox contains wisdom. Socrates is pointing out that true wisdom begins with humility. Only by admitting what we don’t know can we open ourselves to learning. What sounded like a self-contradiction was actually a profound truth about intellectual humility that became more evident over time, hence its enduring status as the “Socratic paradox.” As one commentary notes, the phrase is essentially saying “I neither know nor think I know,” capturing Socrates’ insight that recognizing one’s ignorance is the first step to wisdom.

Nietzsche’s "What Does Not Kill Me"

Friedrich Nietzsche often used striking, paradoxical aphorisms to express his insights. One of his famous maxims is “What does not kill me makes me stronger.” On the surface, it’s counterintuitive—we expect that harmful experiences would only weaken a person. Nietzsche’s paradox asserts the opposite: surviving hardship can build strength of character. This idea was paradoxical in his time because it challenged the ordinary view of suffering. Yet over time the truth of this adage becomes evident: people often grow through adversity, developing resilience and fortitude. Modern psychology even finds some truth in this notion (sometimes called “post-traumatic growth”). Nietzsche compressed a complex insight into a terse paradox, making it memorable and thought-provoking. The contradiction—that pain could yield power—forces us to reflect on how challenges can indeed toughen the human spirit.

Kierkegaard’s Temporal Paradox

Søren Kierkegaard, the 19th-century Danish existential philosopher, expressed a famous paradox about life and understanding: “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” This aphorism appears paradoxical because we cannot literally live life in reverse to understand it. Kierkegaard’s wisdom here is that we gain understanding of our experiences only in hindsight, yet we are compelled to make choices without that full understanding. The truth of this paradox becomes evident as one ages—events that were confusing in youth often make sense later when we look back on them, but at the time we had to live on faith and uncertainty. The saying concisely captures the human condition of learning and growing through time, highlighting the tension between experience and understanding.

Paradoxical Wisdom in Eastern Philosophy

Laozi and Taoist Paradoxes

Eastern philosophical traditions also embrace paradox as a way to point toward deeper truths. In fact, many Eastern sages deliberately frame teachings in paradoxical terms to transcend logical thinking and provoke enlightenment.

The Taoist classic Tao Te Ching by Laozi (Lao Tzu) is rife with paradoxical wisdom. For example, Laozi writes, “Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.” On its face, this statement contradicts itself—if someone truly knows, why wouldn’t they speak about it? And if someone speaks, how could they not know? The paradox actually conveys the Taoist insight that deep understanding cannot be expressed in words. Those who have profound wisdom realize its complexity and are humble or quiet about it, whereas those who talk as if they know everything usually do not have true wisdom.

Laozi also teaches the paradox of wu wei, or “actionless action.” As the Tao Te Ching says: “The Tao does nothing, yet leaves nothing undone.” This puzzling advice urges us to align with the natural flow of things. By not forcing our will (doing nothing contrived), everything falls into place and gets done. What sounds like passivity is actually a subtle strategy for efficient and harmonious action. These Taoist paradoxes encapsulate fundamental truths about knowledge and effort that become clearer with time and practice.

Zen Buddhist Koans

Zen Buddhism is renowned for its use of paradoxical riddles and sayings (koans) as tools for awakening. A classic example comes from the 9th-century Chinese Zen master Linji Yixuan, who told his monks: “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him.” This shocking paradox is not meant literally, but to jar students into letting go of preconceived notions. It seemingly contradicts the veneration of Buddha, yet the true meaning is that one must relinquish their attachment to the idea of Buddha in order to realize enlightenment.

In Zen training, koans like “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” have no logical answer—their purpose is to break the mind free of conventional thinking. The paradox forces the student into a deeper, wordless understanding. Over time, practitioners realize the wisdom in these Zen paradoxes: ultimate truth (often called satori or enlightenment) transcends dualistic logic. Thus, what initially sounds like nonsense becomes a profound insight when one “solves” the koan by intuitive understanding. These concise paradoxes have been used for centuries in Zen as a means to express and transmit wisdom that ordinary discourse cannot capture.

Vedanta’s Non-Dual Insights

The Hindu Vedanta philosophy, especially Advaita Vedanta, frequently describes the ultimate reality (Brahman) in paradoxical terms. One famous verse from the Isha Upanishad proclaims of Brahman: “It moves; It moves not. It is far; It is near. It is within all; It is without all.” This string of contradictions is meant to convey that the absolute truth transcends all binary categories. Brahman (or the Self) is beyond our usual concepts of here vs. there, dynamic vs. static—it encompasses both sides of each pair of opposites.

Another Eastern example comes from the Bhagavad Gita (4:18), which teaches: “One who sees inaction in action, and action in inaction, is intelligent among men.” This paradoxical wisdom counsels detachment in action—the truly wise person can be outwardly busy yet inwardly at peace, and can refrain from egotistical action even while doing their duties. At first this sounds impossible (seeing inactivity within activity), but over time a spiritual practitioner understands it as acting without selfish attachment. Eastern philosophies use such paradoxes to point toward non-dual thinking—a mode of understanding where opposites unify. What seems like a logical contradiction actually guides one to a higher perspective where the paradox is resolved in a deeper truth.

Paradoxes in Religious Teachings

Christianity – Strength in Weakness

Major religious traditions also express fundamental teachings in paradoxical form. These spiritual paradoxes often capture core truths of faith in a concise, memorable way, even if they puzzle the rational mind initially.

The teachings of Jesus abound in paradoxes. For instance, Jesus said, “Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.” This Christian paradox declares that by giving up one’s life (or egoistic self-interest) in devotion to higher ideals, one attains true life. At first it sounds like a riddle—how can losing your life be the way to save it? Over time, believers understand it to mean that selfishly clinging to life leads to spiritual loss, while sacrifice and surrender lead to eternal life or fulfillment. Another Biblical paradox is “the last shall be first, and the first last,” illustrating the inversion of worldly status in God’s eyes. The Apostle Paul also teaches, “When I am weak, then I am strong,” suggesting that human weakness opens one to God’s grace and thus a greater strength. These religious paradoxes encapsulate the counterintuitive wisdom that humility, sacrifice, and vulnerability can lead to spiritual triumph.

Taoism – Wu Wei (Doing by Not Doing)

Taoism, as both a philosophy and religion, treasures paradox. We already saw Laozi’s teaching that the Tao “does nothing yet leaves nothing undone.” In religious practice, this translates to wu wei—effortless action or holy non-interference. The paradox is that one achieves more by letting go and not insisting on one’s own agenda. Taoist sages also speak of the interplay of opposites through the yin-yang symbol—the idea that within each extreme is the seed of its opposite. For example, softness overcomes hardness, emptiness can be useful (an empty cup holds water). These are paradoxes in that they reverse common expectations. Taoist religious texts often say things like “to be reborn, first let yourself die” or “to attain wholeness, embrace your brokenness,” reflecting the belief that opposites complement each other in the Tao. Such teachings sound mysterious, but devotees come to see their truth in lived experience—by “dying” to ego, one is spiritually reborn.

Hinduism – Divine Unity of Opposites

The Hindu tradition contains paradoxes especially in describing the divine. The Upanishadic verse cited above (“It moves and it moves not…”) is a religious description of Brahman, the ultimate reality. Hindu mystics also paradoxically declare that the individual soul is one with God (Tat Tvam Asi—“Thou art That”), even though to the ordinary mind the human and the Divine seem entirely different. In Bhakti (devotional) Hinduism, one finds the paradox of God being both formless and having infinite forms, both transcendent above creation and fully immanent within creation.

Another Hindu paradox is in the Bhagavad Gita when Krishna tells the warrior Arjuna that by renouncing the fruits of action, he can act with perfect effectiveness—inaction in action, as previously mentioned. To a practitioner, these contradictions reveal a higher synthesis: the Divine encompasses all dualities, and true devotion or yoga (spiritual union) arises when one accepts the paradox that in serving others one serves God, in surrendering one’s will one finds freedom. Over millennia, Hindu sages have used such paradoxical sayings to express the indescribable nature of Brahman and the subtle path to realize it.

Buddhism – Emptiness Is Form

Buddhism, especially Mahayana teachings, often frame the profound truth of śūnyatā (emptiness) in a famous paradox: “Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.” This line from the Heart Sutra encapsulates the Buddhist insight that all phenomena are “empty” of independent self-existence, yet that very emptiness is what allows phenomena to exist in interdependence. At first, saying “X is empty” and “empty is X” in the same breath sounds like a logical contradiction. In context, it conveys that the material world and the ultimate void are not two separate realities—they interpenetrate.

Another Buddhist paradoxical teaching is that nirvana (liberation) and samsara (the cyclic world) are not different when seen with true understanding. Zen Buddhism, as noted, is full of pithy paradoxes used as pedagogical tools (e.g. “great enlightenment appears in great doubt”). In Buddhist practice, these paradoxes become clear through meditation experience. The Heart Sutra’s “emptiness is form” line, for example, is chanted by monks who gradually realize that recognizing the emptiness of all things leads to compassionate engagement in the world of form. Thus a statement that initially confounds the intellect becomes an experiential wisdom about the nature of reality.

Historical Examples of Paradoxical Wisdom

Galileo and the Moving Earth

History provides many cases where ideas or principles that sounded contradictory turned out to be true or wise. These examples show that embracing paradox sometimes anticipates truth before it’s widely understood.

In the early 17th century, Galileo Galilei advocated the then-paradoxical idea that the Earth moves around the Sun. This heliocentric model defied common sense (people felt the ground was stationary) and contradicted the authorities of the time. The notion that Earth moved was so controversial that the Catholic Church declared it heresy. To Galileo’s peers, saying the Earth “moves” while we don’t feel it was a perplexing paradox. Yet Galileo’s wisdom—based on observation and reasoning—proved true over time. What seemed a blatant contradiction to everyday experience (a moving Earth that somehow feels stable) is now basic astronomical truth. This historical episode shows that sometimes a truth initially appears impossible or self-contradictory because it challenges accepted frameworks. With evidence and time, the paradox is resolved, and the wisdom in the original insight is recognized. Galileo’s case also popularized the phrase “Eppur si muove” (“And yet it moves”), embodying the paradox of a moving Earth that authorities had tried to deny.

Nonviolent Resistance

In the 20th century, Mahatma Gandhi and later Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. championed nonviolence as a method of fighting injustice. This approach was paradoxical to many observers: how could not fighting back violently overcome powerful, oppressive regimes? It seemed contradictory that refusing to use force could win against those with armies and weapons. History showed the wisdom of this paradox. Nonviolent movements in India and the American Civil Rights struggle succeeded where violent rebellions might have failed or led to worse bloodshed.

Dr. King, in his Nobel Peace Prize lecture, described nonviolence as a “weapon” that “cuts without wounding and ennobles the man who wields it.” That vivid paradox—a sword that heals instead of hurting—proved true in practice, as nonviolence won hearts and changed unjust laws. King noted it was a “weapon unique in history,” capturing how counterintuitive it was perceived to be. Over time, the effectiveness of nonviolence was borne out, and what initially looked like weakness was revealed as a powerful form of action. The lasting social change achieved by nonviolent movements stands as historical evidence that an approach can seem illogical (fighting with peace) yet be profoundly wise.

"The Pen Is Mightier Than the Sword"

This classic proverb, coined in 1839 by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, encapsulates a historical paradox: that ideas and words can have more power than weapons. At first blush, it’s counterintuitive—how could a pen (symbolizing writing or discourse) be “mightier” than a sword (violence)? Yet history repeatedly shows the truth of this saying. Writing, whether in holy texts, philosophical works, or influential literature, has reshaped societies more enduringly than warfare.

For example, pamphlets and newspapers have sparked revolutions, and novels have changed people’s hearts, achieving reforms that brute force could not. The phrase itself is paradoxical wisdom: it uses the contrast of pen vs. sword to express a deeper truth about the enduring power of ideas. Generations who saw military might as the ultimate power eventually recognized that the values and narratives that guide those swords can matter even more. Today, this once-surprising claim is almost self-evident—an example of wisdom that proved itself over time.

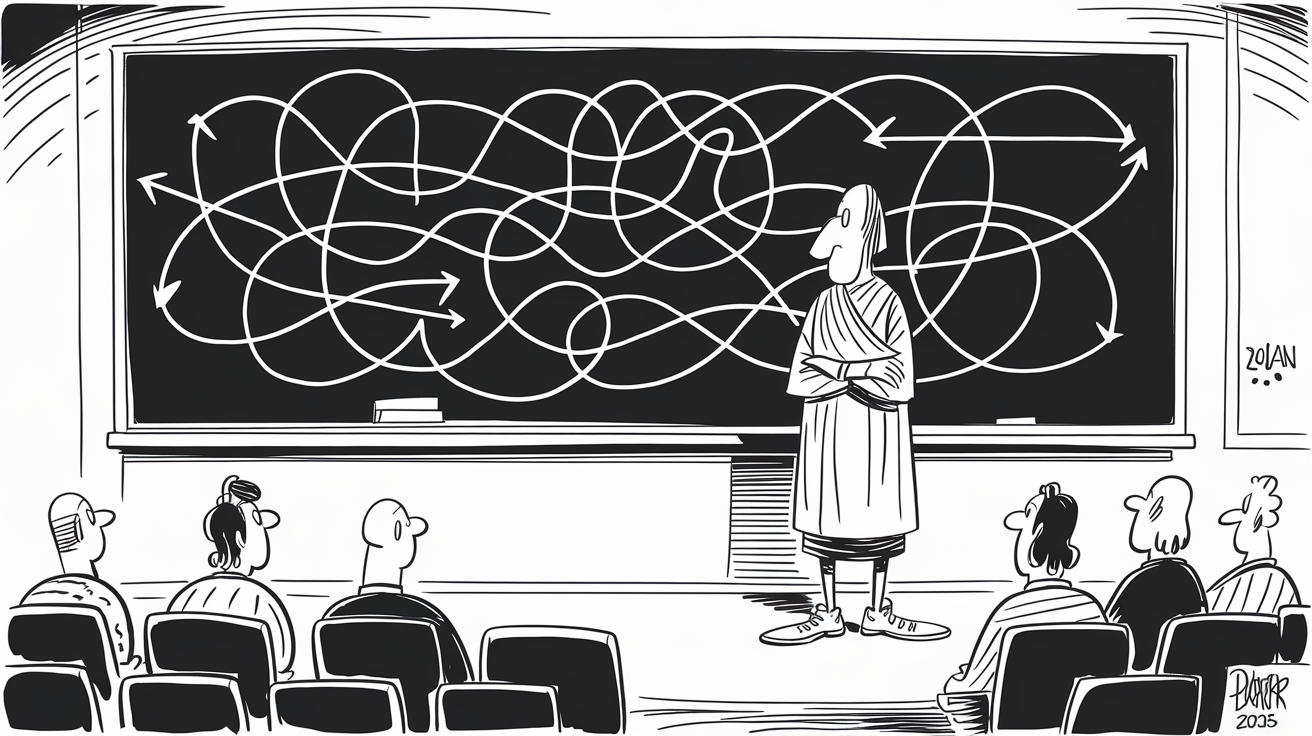

Paradox as a Vehicle for Profound Truth

Why do so many wise sayings and fundamental truths take a paradoxical form? Paradox is a powerful vehicle for wisdom because it captures complexity in a concise, thought-provoking way. A paradox by definition grabs our attention—it makes us stop and think, “How can that be true?” In doing so, it invites us to look deeper. G.K. Chesterton once remarked that “a paradox is truth standing on its head to attract attention.” In other words, when a truth is expressed in an upside-down or contradictory way, it forces people to notice it and wrestle with it. The initial confusion is intentional: it shocks us out of complacency and pushes us toward insight. Many profound teachings could be given a long, logical explanation—but a brief paradox conveys the core insight in a memorable and compact form that often resonates more deeply.

Paradox allows sages to pack wisdom into pithy, almost poetic phrases. For example, “Less is more.” This famous line (originating from a Robert Browning poem in 1855) is only three words long, yet it carries a rich truth about simplicity being superior to excess. Architects, designers, and even those seeking a simpler life have adopted “less is more” as a guiding wisdom, finding that minimalism often yields better results than overabundance. Over time people realized that this apparent contradiction is sound advice—by doing or having less, we achieve more clarity and peace. Similarly, sayings like “You must be cruel to be kind” (sometimes we must cause short-term pain for long-term good) or “The only constant is change” (the one thing that never changes is that everything changes) stick in our minds because they juxtapose opposites in a striking way.

Moreover, paradoxes often reflect the multidimensional nature of truth. Real-life truths are rarely simple; they may involve balancing opposing forces or ideas. Paradoxical expressions embrace that complexity rather than reducing it. A wise paradox doesn’t resolve the tension outright—it lets the tension linger, so that the listener or reader works through it. In that process, one arrives at a more nuanced understanding. For instance, when we hear “strength through weakness” or “freedom through discipline,” we have to think about how those opposites might interact. We come to realize that true strength may involve vulnerability (e.g. the strength of a community arises when individuals admit need and support each other), or that real freedom requires self-discipline (e.g. mastering an art or habit frees you to express yourself). The paradox format succinctly presents the two sides, and the wisdom emerges as we contemplate their relationship.

Finally, paradoxes make wisdom memorable and transmissible. A compact paradox can be easily remembered, shared, and pondered over a lifetime. Religious and philosophical teachers knew that a vivid paradox would be quoted for generations (as indeed Socrates, Laozi, Jesus, and others have been). Because a paradox both confuses and intrigues, it encourages discussion and continuous reflection. Each time one returns to a paradox like “Life is understood backwards but lived forwards,” one may discover a new layer of meaning depending on one’s own life experience. In this way, paradoxical wisdom sayings act like seeds planted in the mind—they might not bloom immediately, but eventually they flower into understanding as the person grows. This enduring quality is why so many cultures encode their most valued insights in paradoxical proverbs and koans.

Conclusion

Across diverse cultures and eras, we repeatedly see that wisdom wears a paradoxical face. From Socrates in ancient Athens to Zen masters in Japan, from the Bible to the Upanishads, the most insightful teachings often defy conventional logic even as they point to a higher logic. What all these paradoxes share is an ability to express a fundamental truth in a concise, powerful way that engages the listener to resolve the apparent contradiction. The phrase “all wisdom is paradox” suggests that to grasp life’s great truths, we must be willing to accept ambiguity and look beyond black-and-white thinking. As the examples from philosophy, religion, and history illustrate, embracing paradox is often the key to unlocking deeper understanding. A paradox might confuse us at first, but ultimately, as one commentator cleverly put it, a paradox is just a truth standing on tiptoe, waiting to be seen once we’re ready to perceive it. By learning to appreciate these “truths on their head,” we open ourselves to the full breadth of wisdom that life has to offer.

Sources

- Plato, Apology – Socrates on knowing his own ignorance

- Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols – “What does not kill me makes me stronger”

- Kierkegaard’s Journals – Life understood backwards, lived forwards

- Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching – “Those who know do not speak…”; “The Tao does nothing, yet leaves nothing undone”

- Linji (Rinzai) Zen Koan – “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him”

- Bhagavad Gita 4.18 – Seeing inaction in action (trans. Prabhupada)

- The Bible, Matthew 16:25 – Lose life to save it

- Isha Upanishad, verse 5 – Description of Brahman (trans. Panoli)

- Heart Sutra – “Form is emptiness, emptiness is form”

- UCLA News – Heliocentrism as heresy in Galileo’s time

- Martin Luther King Jr., Nobel Lecture (1964) – On nonviolence as a sword that heals

- Bulwer-Lytton (1839) – “The pen is mightier than the sword” explained

- Browning (1855) – “Less is more” as a principle of simplicity

- Quote Investigator – Paradox as truth on its head (attributed to G.K. Chesterton)