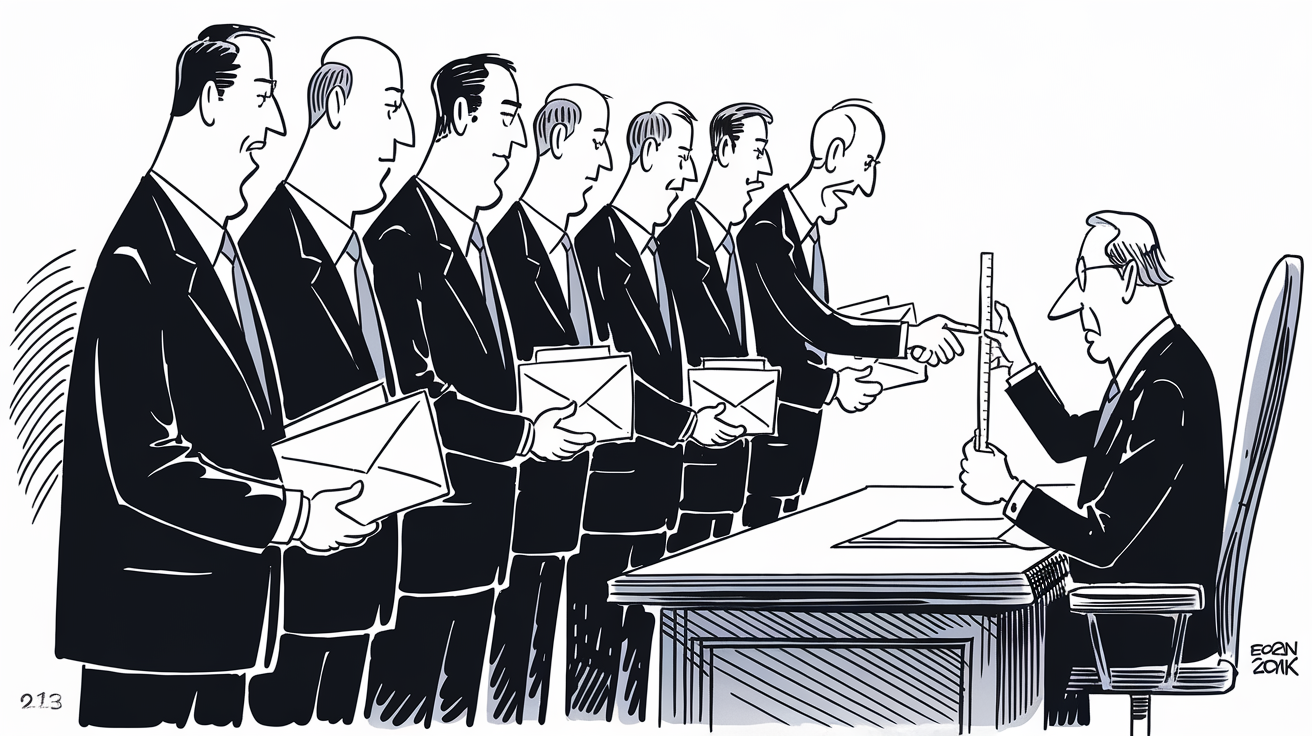

Is the lowest bid always the winner?

Why Estimating the Second-Lowest Bid is Key in Low-Bid Auctions

Low-Bid Auctions in a Nutshell

In a low-bid auction (such as a government contract tender), the contract is awarded to the lowest bidder who meets all requirements. Essentially, companies submit sealed bids with the price at which they’re willing to do the job, and the one offering the lowest price wins the contract. The second-lowest bid is the lowest losing bid – the price offered by the runner-up competitor who just missed winning. This second-lowest number is crucial because it represents the threshold you needed to beat to win. Understanding and estimating this number can mean the difference between winning with healthy profits or losing the bid (or winning but leaving money on the table).

The Importance of the Second-Lowest Bid (Lowest Losing Bid)

Winning by a Small Margin

In competitive bidding, you don’t need to dramatically underbid everyone else; you just need to be a hair lower than the second-lowest bidder. The goal is to win by the smallest possible margin. Why? If you bid much lower than necessary, you’ll still win, but you sacrifice profit that you could have kept. If you bid even a tiny bit above the second-lowest bid, you lose the contract entirely. In other words, the second-lowest bid is the price to beat – the cut-off point for winning. Your bid only needs to be slightly below that cut-off. Any lower than that is essentially excess discount you gave away.

Maximizing Profit

The second-lowest bid also sets the ceiling for your own bid. Ideally, you want to bid just below this number to win while charging as much as possible. Every dollar you drop below the next competitor’s bid is a dollar of profit forfeited. In fact, the difference between your winning bid and the second-lowest bid is often called “money left on the table,” because it’s money you could have earned if you had bid closer to your competitor’s price (The Effect of the Level of Competition). Think of this difference as your foregone profit – profit you gave up in order to bid lower and secure the win. The smaller that gap, the more of the contract value you keep for yourself. Thus, accurately estimating the second-lowest bid helps you minimize that gap: you still come in first, but you don’t undercut your price more than needed.

Common-Sense Analogy - A Race for the Lowest Price

Imagine a race where the goal is to finish with the lowest time. To win, you only need to run slightly faster than the second-fastest runner. If you sprint far ahead of everyone, you win by a huge margin – but you also expend unnecessary energy. In bidding terms, sprinting too far ahead is like bidding far below the next lowest competitor: you win easily, but you give away profit. Conversely, if you run just a fraction faster than the second runner, you still win but with minimal wasted effort. In the same way, bidding just a little bit lower than the second-lowest bid wins you the contract without cutting your price more than necessary.

Real-World Example

Suppose three firms bid on a project: Firm A bids $1,000,000; Firm B bids $1,100,000; Firm C bids $1,300,000. Firm A is the lowest bidder and wins at $1,000,000, and Firm B is the second-lowest at $1,100,000. Firm A beat B by $100,000. But consider this – if Firm A had bid $1,090,000, it would still be the lowest bidder (just $10,000 below Firm B) and would earn $90,000 more revenue on the contract. That $90,000 is profit left on the table by bidding $1,000,000 when they only needed to bid slightly under $1,100,000. On the other hand, if Firm A had bid above $1,100,000 (even $1,101,000), it would lose to Firm B. This example shows that the sweet spot is just under the second-lowest bid: that’s the number you want to predict as closely as possible.

Why It’s The Key Number

In summary, the second-lowest bid represents the ideal target price for a winning bid. If you could magically know your closest competitor’s price in advance, you’d set your bid a hair below it and win with maximum profit. In fact, some auction designs recognize the importance of this number: for example, in certain automated reverse auctions (like those for online ads), the winner (lowest bidder) actually gets paid at the price of the second-lowest bid (Auction - Understanding How the Auction Process Works). This ensures the winner doesn’t undersell unnecessarily. While government contracts typically don’t use this “second-price” rule (you get paid what you bid, not what the runner-up bid), the principle is the same – to win and profit, you should aim to be just below that second-lowest figure.

Strategies for Estimating the Second-Lowest Bid

Accurately estimating the second-lowest bid is challenging – after all, you don’t know competitors’ bids beforehand – but you can make informed predictions. Here are strategies and factors to consider to predict that critical number and position your bid for victory with healthy profits:

Study Competitor Behavior: Research your competitors’ bidding patterns and business motives. Do they tend to bid very aggressively (low margins) or do they leave comfortable margins? If a particular competitor historically undercuts everyone with rock-bottom prices, you’ll need to anticipate a very low second-best bid. On the other hand, if competitors generally aim for moderate profits, the second-lowest bid may be higher. Also consider competitors’ situations – a company that is hungry for work might bid lower than usual, whereas one that’s swamped with projects might bid higher. Understanding who you’re up against and their likely approach helps bracket the range of probable bids.

Review Historical Bidding Trends: Past bids on similar projects are a goldmine of information. If you have access to bid tabulations or award information from previous, comparable contracts, examine the spread between the winning bid and the second-lowest bid. Historical data might show, for instance, that in your industry the lowest and second-lowest bids are often only a few percentage points apart. If historically the second-lowest tends to be, say, 2% above the winner, that gives you a clue on how tight you should price. Also note how many bidders participated and how that affected the spread. A consistent pattern (like the runner-up always being within a tight margin) means you should plan to bid very close to what you estimate the runner-up will bid. If there’s an outlier case where the lowest bid was much lower than the pack, be cautious – the lowest bidder may have made an error or accepted an extremely low margin. As a bidder, you generally don’t want to be too far below the second-lowest; a huge gap could mean you miscalculated costs or left profit on the table (and even the contracting agency might question if your ultra-low bid is realistic). Use historical trends to gauge a reasonable range for the second-best offer on the project.

Analyze Market Conditions: The broader market environment heavily influences how competitors bid, which in turn affects the second-lowest bid. Ask yourself: Are market conditions driving prices up or down? In tight economic times or slow markets (when fewer projects are available), contractors may bid more aggressively just to win work, pushing the second-lowest bid downward. In a booming market with plenty of jobs to go around, companies might bid higher (with comfortable profit margins), knowing there’s ample work – which raises the likely second-lowest bid. Also consider input costs and supply chain conditions: if materials and labor costs have recently spiked for everyone, all bids will be higher overall than last year’s, but the relative gap between bidders might remain consistent. If new competitors enter the market or existing ones drop out, the level of competition changes. More bidders generally means a tougher fight and a lower second-lowest price, whereas fewer bidders might lead to a higher second-lowest bid because there’s less pressure to slash prices.

Use an “Engineer’s Estimate” or Cost Benchmark: In many government tenders, an engineer’s estimate or similar cost benchmark is provided or can be inferred. This is essentially what the buyer expects the project to cost. While competitors’ bids will fluctuate around this, it offers a reference point. If you suspect most competent bidders will be near the engineer’s estimate, the second-lowest bid might be just above that figure. Your own internal cost calculations plus a reasonable profit margin should also be compared against such benchmarks. If your cost is much lower than typical, you might have room to bid under everyone; if it’s higher, you may need to trim margins or find efficiencies to get down near where the second-lowest is likely to be. In short, know the ballpark price for the job from an industry standpoint – it will help you sense how low others might go.

Aim for a Narrow Win (Include a Safety Buffer): Once you’ve gathered intelligence on competitors, past bids, and market conditions, formulate an estimate for the second-lowest bid and then decide how much lower you should go to safely win. It’s wise to include a small safety buffer below your best guess of the competitor’s price. For example, if you estimate the next-best competitor will bid $500,000, you might aim for something like $490,000 or $495,000 – just enough of a gap to ensure you come in below them, but not much lower. The buffer accounts for the uncertainty in your estimate and for any last-minute shifts. Essentially, you want to beat the second-lowest by a slim margin, not by a wide gulf. One practical method is to decide on the minimum profit margin you’re willing to accept, and use that to set your floor price. Then, if your competitor-based estimate of the second-lowest allows it, bid at a price that gives you slightly above that minimum margin. It’s a balancing act – too high and you risk losing, too low and you chip away at your profit.

Learn from Each Bid Outcome: Estimating the second-lowest bid is an iterative learning process. After each auction or bid round, review the results. How did your estimate of the second-lowest compare to reality? If you won, was your bid significantly lower than the next bidder (meaning you overcut)? Or did you just barely win? If you lost, how far above the winning price were you, and was that the second-lowest? Over time, tracking these outcomes will sharpen your ability to predict competitors’ bids. You might notice, for example, that one competitor consistently bids very close to your prices, or that the average gap between first and second place in your industry is, say, 3%. These insights allow you to fine-tune your future estimates. Also, keep an eye on who the second-lowest bidder tends to be – understanding their identity and behavior can improve your predictions next time you face them. In essence, treat each bidding round as intelligence gathering to improve your second-lowest bid estimates going forward.

Conclusion: Hitting the Sweet Spot

In low-bid auctions, success comes from hitting the sweet spot – just below the other guy’s price. The second-lowest bid is the critical number that defines this sweet spot. By focusing on estimating that number, you ensure that your own bid is competitive enough to win but not lower than it needs to be. This maximizes your profit on the contract while still securing the award.

It boils down to a simple idea: you want to win by paying as little “price” (foregone profit) as possible for the win. All the strategies – analyzing competitors, studying past trends, gauging the market, and adding a safety buffer – are aimed at one goal: figuring out what that next-best offer will likely be, and positioning yourself just under it. When you can accurately anticipate the lowest losing bid, you bid with confidence that you’re offering the buyer a great price and leaving yourself a fair profit. This is how savvy contractors thrive in the competitive world of government contracts: by always keeping an eye on that runner-up bid, they consistently win contracts and make money doing so.

Key Takeaway: In a low-bid auction, knowing where the finish line really is (the second-lowest bid) lets you cross it first and stride into the winner’s circle profitably. Focus on that number, bid strategically, and you’ll maximize your chances of winning and profiting from every contract.