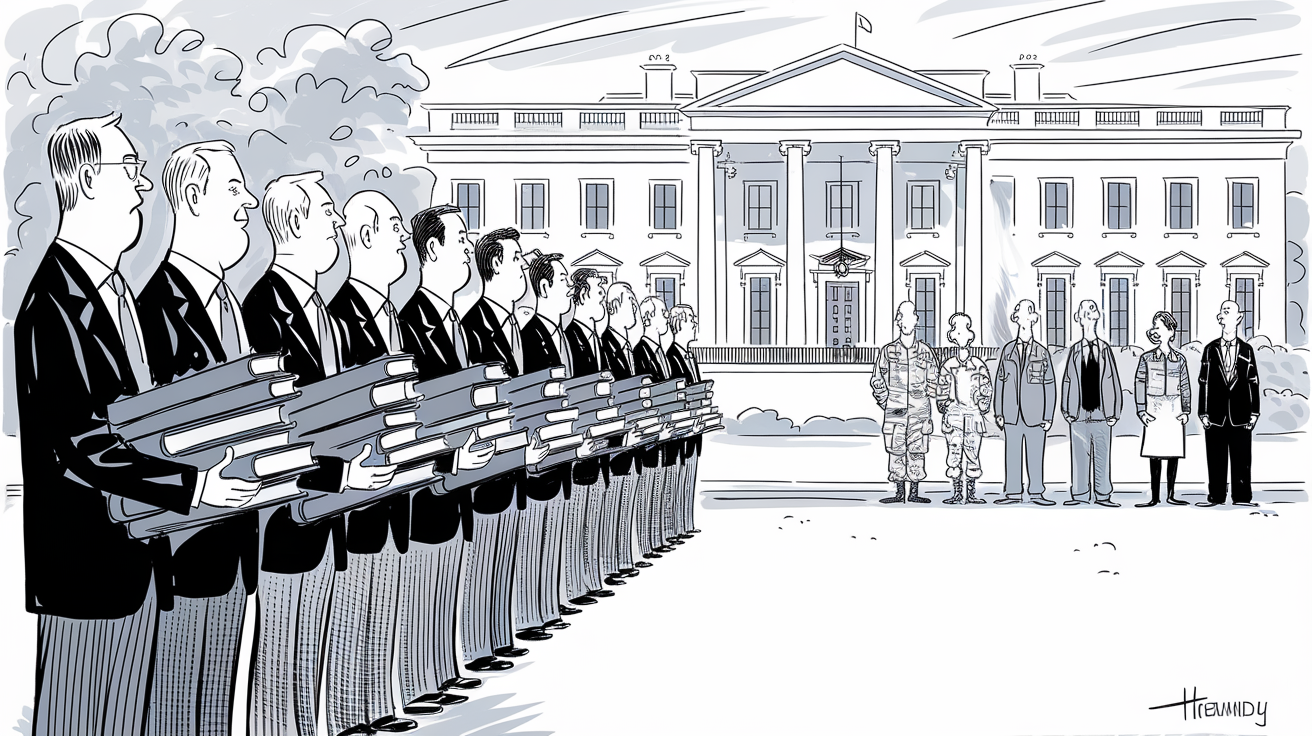

Do Lawyers Still Dominate Presidential Candidates?

Historically, a majority of U.S. major-party presidential nominees have come from the legal profession. In fact, over half of all U.S. presidents (26 out of 45) were trained as lawyers (The Long History of America’s Lawyer Presidents | Blog | Lawline), and roughly 60% of major-party nominees in history had legal backgrounds (either as attorneys or judges). By contrast, a significant minority have come from non-legal backgrounds – including military generals, businessmen, and others. Out of 63 individuals who have been Democratic or Republican presidential nominees through 2020, 36 were lawyers by profession (57%) and 27 were not. When counting each nomination (including candidates who ran multiple times), about 61% of all major-party candidacies were led by lawyers.

Overview of Lawyer vs. Non-Lawyer Candidates

Over half of all U.S. presidents trained as lawyers, and this professional background long dominated American politics. For example, founding-era presidents like Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe studied and practiced law before entering politics, as did Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk in the Jacksonian era (The Long History of America’s Lawyer Presidents) (Which U.S. Presidents Were Lawyers? - Civille). This trend carried into the formation of the Democratic Party in the 1830s – every Democratic nominee from 1828 through 1852 had a legal background (Jackson, Van Buren, Polk, Lewis Cass, Franklin Pierce, etc.).

As the country evolved, non-lawyer candidates began to appear. Military heroes became political contenders (e.g. Gen. Winfield Scott and Gen. Ulysses S. Grant), and by the late 19th and early 20th centuries a few businessmen and career politicians without law degrees also made bids. Still, through the 19th century and into the early 20th century, lawyers remained dominant among nominees of both major parties. By the mid-20th century, 27 U.S. presidents had worked as lawyers (and 9 had been career generals) (List of presidents of the United States by previous experience).

The table below summarizes the overall success rates of lawyer vs. non-lawyer candidates:

| 1828–2020 Major-Party Nominees | Lawyers | Non-Lawyers |

|---|---|---|

| Total Nominations | 56 | 35 |

| Won Presidency (elections won) | 30 | 17 |

| Success Rate (win percentage) | ~54% | ~49% |

Table: Election outcomes for lawyer vs. non-lawyer candidates. (Each nomination counted; some individuals ran more than once.) Overall, candidates with legal backgrounds have won about half of their races (~54%), versus ~49% for those without legal training. In other words, lawyers have been only slightly more likely to win the presidency than non-lawyers over the long run. The small difference suggests that while many nominees have been lawyers, having a law degree has not guaranteed victory – and several non-lawyers have been quite successful (for example, General Dwight D. Eisenhower and businessman Donald Trump both won the presidency without any formal legal background (Dwight D. Eisenhower | Biography, Cold War, Presidency, & Facts) (History of Donald Trump | Humans - Vocal Media)).

Trends by Decade and Party Affiliation

The proportion of lawyer-candidates has shifted markedly over time, with some distinct eras. The visualization below shows the percentage of major-party nominees each decade who were lawyers, broken down by party:

(image) Percentage of Democratic (yellow) and Republican (orange) presidential nominees who were lawyers, by decade. In the early 1800s, Democratic nominees were uniformly lawyers (100%), while the Republican Party did not exist until the 1850s.

Several patterns stand out:

Early 1800s (1820s–1840s): The Democratic Party’s candidates were almost all lawyers by profession. From Andrew Jackson through James Buchanan, Democratic nominees typically had extensive legal careers (Jackson was a frontier attorney and judge, Martin Van Buren was a state attorney general and lawyer, and Polk and Pierce likewise practiced law). In this era, legal training was considered essential for statesmen. There was no Republican Party yet, but other major candidates of the early 19th century (Federalists, Whigs, etc.) were similarly often lawyers or statesmen; for instance, Abraham Lincoln – the first Republican president (1860) – was himself a self-taught lawyer.

Mid/Late 19th Century (1850s–1890s): Both Democrats and the new Republican Party continued to favor lawyer-candidates, though a few notable exceptions appeared. Republicans had a mix: e.g. John C. Frémont (the GOP’s first nominee in 1856) was not a lawyer (he was an explorer and army officer), whereas Abraham Lincoln (1860) and most late-1800s Republicans (Hayes, Garfield, Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, etc.) were lawyers. The Democrats in this period stuck largely with lawyers as well – from 1856 through 1896, the vast majority of Democratic nominees (Buchanan, Stephen Douglas, Horatio Seymour, Samuel Tilden, Grover Cleveland, William J. Bryan, etc.) had legal backgrounds, with only an occasional non-lawyer (e.g. Horace Greeley in 1872 was a newspaper editor). As the chart shows, both parties in the Gilded Age had 60–100% of their nominees being lawyers per decade.

Early 20th Century (1900–1940): Lawyer-candidates were still common, but we see the start of more professional diversity. Democrats from 1900–1930s were mostly lawyers (e.g. Alton Parker 1904, Woodrow Wilson – who trained in law – 1912/16, John W. Davis 1924, Franklin D. Roosevelt 1932 all had legal trainin (Which US Presidents Were Lawyers? - Legal Language Services)). However, Democrats did nominate a couple of non-lawyers in this era (e.g. James Cox (1920) and Al Smith (1928) were career newspapermen/politicians without law degrees). Republicans between 1900 and 1940 alternated between lawyers and non-lawyers. For instance, Theodore Roosevelt (1904) and Herbert Hoover (1928) had non-legal backgrounds, whereas William H. Taft (1908) and Charles Evans Hughes (1916) were prominent lawyers/jurists. By the 1930s, the GOP had two non-lawyer nominees in a row – Hoover and Alf Landon (1936) – making the 1930s the first decade where 0% of Republican nominees were lawyers. In short, by the early 20th century, most Democratic nominees still tended to be lawyers, while Republicans showed a bit more variety, occasionally turning to business or military leaders.

Post–World War II Era (1950s–1970s): This period saw significant shifts in each party’s profile. Immediately after WWII, both parties broke the mold: The Republicans nominated General Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952, a career military hero with no prior legal or political office. The Democrats in 1952 and 1956 ran Adlai Stevenson II, a former lawyer (and Illinois governor) – but then in the 1960s and 70s, Democrats shifted to a slate of non-lawyer candidates. Notably, John F. Kennedy (1960) had a background in journalism and politics, Lyndon B. Johnson (1964) had been a teacher and career politician, Hubert Humphrey (1968) was a pharmacist-turned-politician, and Jimmy Carter (1976) was a Naval officer and peanut farmer-turned-politician. None of those Democratic nominees in the 1960s–70s were lawyers, while Republicans in the 1960s–70s often nominated lawyers (both Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford were lawyers by training). The 1970s particularly stand out: in the 1972 and 1976 elections, 100% of GOP nominees were lawyers (Nixon and Ford), while 0% of Democratic nominees were (McGovern and Carter). This was a flip from the 19th-century pattern and a unique moment where Republicans appeared as the party of lawyer-politicians and Democrats as the party of “outsider” backgrounds.

Recent Decades (1980s–2020): A near-complete reversal emerged by the late 20th century. Since the 1980s, Democrats have overwhelmingly nominated lawyers, while Republicans have mostly chosen non-lawyers. For example, every Democratic nominee from 1984 through 2020 except one (Al Gore in 2000) had a law degree or legal career – including Walter Mondale (1984), Michael Dukakis (1988), Bill Clinton (1992/96), John Kerry (2004), Barack Obama (2008/12), Hillary Clinton (2016), and Joe Biden (2020), all of whom are attorneys. On the other hand, Republican nominees since the 1980s have mostly been from outside the legal profession. The GOP turned to a former actor (Ronald Reagan, 1980/84), a CIA director/businessman (George H.W. Bush, 1988/92), a business executive (Mitt Romney, 2012, who earned a law degree but made his career in business), and a real-estate mogul/TV personality (Donald Trump, 2016/20), none of whom were practicing lawyers (Ronald Reagan: Biography, 40th U.S. President, Politician, Actor) (History of Donald Trump). The only Republican presidential nominee with a prominent legal background in the last 40+ years was Bob Dole (1996), who had been a lawyer early in his career. Thus, by the 21st century the Democratic Party has leaned heavily on candidates with legal resumes, whereas the Republican Party has favored candidates with military or business credentials.

Historical context: The shift from the “lawyer-statesman” model (common in the 1800s) to a more diverse set of backgrounds reflects broader changes in society. In the early 1800s, legal expertise was practically a prerequisite for national leadership – lawyers were seen as skilled orators and thinkers. By the post-WWII era, other forms of experience gained public esteem – for example, military leadership (WWII generals) or business success were seen as proving one’s executive abilities. The parties responded to these perceptions: e.g., Republicans won big with war hero Eisenhower in 1952, and later with celebrity-turned-politician Reagan in 198. Democrats, after some experimentation in the 1960s–70s, returned to emphasizing legal/government experience. Meanwhile, Republicans increasingly capitalized on outsider appeal or military credentials. These choices illustrate how the appeal of a candidate’s professional background has shifted with the times – from lawyerly eloquence in the 19th century, to generalship in the mid-20th, to diverse forms of executive experience in the modern era.

Success of Lawyers vs. Non-Lawyers

Being a lawyer has not automatically made candidates more successful at winning elections – successful nominees have come from both groups. Overall, lawyer nominees have a slight edge in raw numbers of wins (lawyers have won 30 presidential elections vs. 17 wins by non-lawyers in major-party contests), but this is largely because lawyers were more common in the first place. In percentage terms, their win–loss rates are fairly close (about 54% for lawyers vs. 49% for non-lawyers).

Notably successful non-lawyers: A number of non-lawyer candidates have won the presidency, often in pivotal elections. For example, Dwight D. Eisenhower, a five-star general with no legal or political office background, won back-to-back elections in the 1950s by wide margin. Ronald Reagan, the first former Hollywood actor to become president, won landslides in the 1980s. More recently, Donald Trump, a businessman and television personality with no prior government service, won the 2016 election. These victories show that voters have at times favored leadership experience outside the courtroom.

Prominent lawyer-candidates (and outcomes): Most U.S. presidents have indeed been lawyers by trade, from Abraham Lincoln (an Illinois attorney) to Franklin D. Roosevelt (who had practiced law in New York) to Bill Clinton (Yale Law graduate and Arkansas attorney general). Many lawyer-candidates have been successful – e.g., Woodrow Wilson (won in 1912 and 1916, having briefly practiced law before academia), Franklin D. Roosevelt (won four terms, had legal training), and Barack Obama (won in 2008 and 2012, former law professor). However, there have also been notable lawyer nominees who lost their races, indicating that a legal résumé was no guarantee of victory. For instance, Charles Evans Hughes (Republican, 1916) was a Supreme Court Justice yet narrowly lost to Wilson; Adlai Stevenson II (Democrat, 1952 and 1956) was a lawyer who lost twice to Eisenhower; and Hillary Clinton (Democrat, 2016) was a Yale-educated attorney who fell short against Trump. Some non-lawyer candidates who lost include Barry Goldwater (1964) and Al Smith (1928), showing that non-legal background is also not a magic formula. In short, electoral success has depended on many factors beyond profession – war records, economic conditions, charisma, and campaign strategy – not just whether a candidate was a lawyer.

Party Differences in Candidate Backgrounds

When comparing the Democratic vs. Republican track records, clear differences emerge in different eras:

19th century: Both parties (Democrats, and the Whigs/Republicans) favored lawyers. The Democrats especially were led by a “lawyer-politician” class (e.g. every Democratic president from 1828 to 1860 was an attorney). Republicans (founded in the 1850s) also leaned that way initially – their first successful candidate, Lincoln, was famously a lawyer. Thus, in the 1800s there wasn’t a stark partisan split on professions; being a lawyer was seen as the standard qualification for statesmanship in either party.

Early 20th century: Still no strong partisan divide – both parties ran many lawyers, with a few exceptions in each. For example, in 1924 the Democrats nominated John W. Davis (a Wall Street lawyer) while Republicans had Calvin Coolidge (a lawyer); in 1928, by contrast, Democrat Al Smith and Republican Herbert Hoover were both non-lawyers. Each party was willing to nominate a non-lawyer under the right circumstances, but lawyers were common on both tickets.

Late 20th century (post-1980): A partisan divergence took hold. The Democratic Party became much more likely to choose lawyers – often individuals who built careers in law and then politics (e.g. Mondale, Dukakis, Clinton, Obama, Hillary Clinton, Biden). Meanwhile, the Republican Party more frequently turned to non-lawyers, tapping candidates with military service or business/outsider backgrounds (Reagan, the Bushes, McCain, Trump). By the 2000s, it was almost a party stereotype that Democratic candidates were seasoned lawyers, whereas Republican candidates were often from outside the legal profession. For instance, 2016 featured a contest between two starkly different résumés: Hillary Clinton, a former attorney and Secretary of State, versus Donald Trump, a businessman with no legal or government experience. This partisan trend persists – in 2020, Democrats nominated Joe Biden (lawyer-turned-Senator) and Republicans renominated Trump (businessman).

Impact on elections: Neither party’s preference has proven universally superior in elections. Democrats won many races with lawyer-candidates (e.g. Clinton and Obama’s victories), but also lost in 2016 with a highly experienced lawyer (Clinton). Republicans won with non-lawyers like Eisenhower, Reagan, and Trump, but also lost in 1992 and 1996 with non-lawyers (George H.W. Bush and Bob Dole) losing to lawyer Clinton. The 1970s provide an interesting contrast: the lawyer-heavy GOP lost in 1976 (Ford, a lawyer, lost to Carter, a non-lawyer), but the tables turned in 1980 when a non-lawyer Republican (Reagan) defeated a non-lawyer Democrat (Carter). These examples underscore that while the professional makeup of candidates differs by party in modern times, success has depended on context. Each party’s strategy has worked in some elections and failed in others.

Conclusions and Historical Reflections

Throughout U.S. history, lawyers have been a mainstay of presidential politics, especially in the republic’s first century. The early “lawyer-statesman” archetype set a lasting precedent – even today, many candidates hold law degrees as a badge of credibility. Over time, however, the appeal of alternative career paths grew. By the 20th century, Americans proved willing to elect engineers, soldiers, businessmen, and actors to the nation’s highest office. The proportion of lawyer candidates has fluctuated by decade, generally declining in the mid-20th century and then rising again for Democrats late in the century, even as Republicans moved the other way. This divergence after WWII highlights how the two parties responded differently to social currents – one valuing institutional experience, the other often valuing outsider status or military leadership.

In terms of outcomes, being a lawyer vs. not has not decisively determined who wins the White House. Lawyer candidates have won many elections – but so have non-lawyers, especially when their personal story or the national mood favored an outsider. Each era of U.S. history brought its own expectations for leadership. In the 19th century, a grounding in law was seen as essential for navigating the young nation’s legal framework. In the 20th century, crises like World War II and the Cold War elevated candidates with military or executive skill. In the 21st century, communication skills and outsider credibility can propel a candidate without traditional credentials. The major parties’ nominees reflect these shifting priorities.

To summarize: Democratic and Republican presidential candidates have evolved from almost uniformly lawyers in the 1800s to a mix of professions in recent decades. Democrats today still lean into the tradition of the lawyer-politician (as seen with nominees like Obama and Biden), while Republicans have often broken from it (opting for candidates like Reagan and Trump). The success of any candidate, lawyer or not, has ultimately hinged on the person and the moment – not just their profession. The dynamic trends in candidates’ backgrounds offer a fascinating window into American political history, showing how each generation reinterprets the qualities deemed necessary to lead the nation.

Sources: Historical data compiled from U.S. presidential election records and biographical sources. Notable references include the American Bar Association and U.S. State Department notes on presidents’ professions (e.g. 25–27 presidents were lawyers, over half of all presidents), as well as biographies of individual candidates (e.g. Eisenhower’s military career, Reagan’s acting career, Trump’s business background). These illustrate the professional makeup of candidates and provide context for the shifts observed across different periods of U.S. history.