History of Mining in Goa, India

Goa’s iron ore mining industry has traversed a dramatic journey – from its quiet early days under Portuguese rule to becoming a key export sector, and then facing shutdowns amid legal battles and environmental concerns. This report chronicles the history of iron ore mining in Goa, highlighting major phases such as the Portuguese era, the post-1961 transition, the China-driven boom, the investigations into illegal mining, landmark court judgments, and the recent shift to auction-based mining. The narrative is structured chronologically, combining factual detail with the unfolding legal saga, and is supported by citations for verification.

Early Mining in Goa

Reports suggest that mineral deposits in Goa were known for centuries. Local legends even mention Jain residents extracting gold in ancient times (History of Mining in Goa – The Goenchi Mati Movement). However, iron ore extraction remained limited until the late 19th and early 20th century. The first documented mining concession in Goa was granted in 1905 to a businessman from Constantinople (Istanbul), marking the modest beginning of Goa’s mining industry. A few years later, in 1910, a French company attempted to mine manganese in Goa, planning a railway to transport ore, though large-scale operations did not immediately follow.

Significant mining activity in Goa began in the mid-20th century. In 1929, under Portuguese colonial law, the first official mining lease (concession) was granted (History Timeline). By the 1940s, enterprising Goan families and companies started mining iron and manganese ore on a larger scale. Notably, a test shipment of Goan iron ore was sent to Japan in 1939 under the supervision of Vishwasrao Chowgule, a pioneer of Goa’s mining industry (Portuguese Authorities In Goa: Portugal turns to mining to boost economy | Goa News - Times of India). This proved that Goan ore could find international markets, setting the stage for an export-oriented industry.

The Portuguese Era (1940s–1961)

After World War II, mining in Goa accelerated rapidly. The Portuguese colonial government, which still ruled Goa until 1961, actively encouraged mining to boost the territory’s economy. One reason was to demonstrate that Goans could enjoy a higher standard of living under Portuguese rule than Indians did in independent India. Throughout the 1950s, the colonial administration issued mining concessions liberally. In 1947 (the year India became independent, though Goa was still Portuguese), 17 mining leases were in operation; this number grew to 42 by 1950. By 1953, there were 144 active mining leases, and mechanized mining techniques were introduced around this time to increase production.

Goa’s iron ore output surged in the late 1950s. The 1955 economic blockade imposed by India (to pressure Portugal to relinquish Goa) pushed the Portuguese to intensify mining as an alternate revenue source. In the single year 1960, an astonishing 596 new mining leases were granted in Goa. By the time Goa was liberated from Portuguese rule in December 1961, over 700 mining concessions had been sanctioned in total. Iron ore exports had swelled to about 6.5 million tonnes per year by 1961, with Japan and Western Europe being major buyers of Goa’s low-grade iron ore. Mining had transformed from a minor activity into a cornerstone of Goa’s economy during the Portuguese era. This rapid expansion, however, set the stage for future challenges in regulating the sector.

Post-Liberation Changes (1961–1987)

When India annexed Goa in December 1961, the thousands of existing Portuguese mining concessions posed a legal and administrative challenge. For a time, the mines continued operating under the old concession system even as Goa became an Indian territory. The Indian government gradually moved to bring Goa’s mining under national mining laws. A crucial reform came with The Goa, Daman and Diu Mining Concessions (Abolition and Declaration as Mining Leases) Act, 1987, enacted on 23 May 1987. This law abolished the Portuguese-era perpetual concessions and converted them into fixed-term mining leases under India’s legal framework. Under the Act, all former concessions were deemed to be mining leases effective from the date of Goa’s liberation, with a 20-year lease period (retroactively 1961–1981, later extended to 2007). The erstwhile concession-holders were compensated by the government, and from 1987 onward the plethora of Indian laws – including environmental and labor regulations – fully applied to mining operations in Goa.

During the 1960s and 1970s, as Goa integrated with India, its mining industry continued, though it experienced cycles of boom and bust. The first two decades after liberation saw infrastructure improvements – for example, companies like Chowgule and Salgaocar mechanized mining processes, built barges and transshipment facilities, and even set up India’s first iron ore pelletization plant in Goa in 1967. By the late 1970s, however, global iron ore demand dipped, leading to a bust cycle. Many mines became barely profitable in the late 1970s, and again in the early 1990s, when another downturn hit. During these lean periods, some mining operators allegedly began cutting corners to save costs, giving rise to questionable practices in mining and exports. It is likely that illegal mining practices – such as under-reporting of production or encroachment beyond lease areas – took root during these hard times.

Despite the downturns, mining remained an important livelihood for thousands of Goans. By the mid-1980s, the industry had recovered somewhat, only to face the regulatory upheaval of the 1987 Act. Many mine owners legally challenged the Act’s provisions (arguing against the termination of their perpetual rights), and some of those disputes lingered in courts for years. Nonetheless, mining operations continued under the new regime. By the end of the 1990s, with global commodity markets rebounding, Goa’s miners were poised for another boom – one that would soon be fueled by unprecedented demand from China.

The China Commodity Boom (2000s)

The early 2000s brought a commodity super-cycle, driven largely by China’s rapid industrial growth. Iron ore prices and demand soared worldwide, and Goa – with its low-grade iron ore in abundant supply – found itself at the center of a lucrative export rush. Around 2003–2004, Chinese steel mills began importing huge quantities of iron ore, including lower-grade ore that earlier might have been considered waste. Goa’s miners responded to the opportunity with a mad rush to extract as much ore as possible and ship it to China. Iron ore production in Goa skyrocketed – from just about 5 million tonnes in the late 1990s to over 45 million tonnes by 2010 (peaking around 2007–2012). Almost 99% of Goa’s iron ore was exported, since the local Indian steel industry preferred higher-grade ore from other regions. By 2010–11, mining contributed roughly 20% of Goa’s Gross State Domestic Product, underlining its central role in the state’s economy.

However, this breakneck expansion came at tremendous environmental and social cost. Unregulated and illegal activities became commonplace during the boom. There were frequent reports of mines expanding into forest areas without permits, extracting beyond approved quantities, and dumping waste soil into rivers and fields. The transportation of ore by thousands of truck trips and barges led to pollution and public health concerns. Malpractices were commonplace – as one account noted, the boom period was accompanied by widespread violations of law in collusion with authorities. Local communities and activists grew alarmed at the environmental degradation: agricultural productivity fell in mining zones, water sources were contaminated by silt, and once-tranquil villages of Goa’s interior experienced noise, dust, and disruption.

Starting in the late 2000s, a series of Public Interest Litigations (PILs) were filed in courts, and some mines were shut down temporarily on grounds ranging from lack of environmental clearance to encroachment on government land. These piecemeal actions, however, did little to halt the overall frenzy. The tipping point came when the Indian central government appointed a Commission of Inquiry headed by Justice M.B. Shah in 2010 to investigate illegal mining in several states, including Goa. As the commission undertook its fact-finding, it became evident that Goa’s mining boom was a textbook case of unrestricted, unchecked and unregulated mining, enabled by systemic corruption. The stage was set for a major reckoning.

Shah Commission Report and the 2012 Ban

In September 2012, the Justice M.B. Shah Commission’s report on Goa’s mining was tabled in the Indian Parliament – and its findings were explosive. The Shah Commission estimated that the iron ore mining scam in Goa was worth about ₹35,000 crore (roughly USD 5 billion) in losses to the public exchequer. This staggering figure represented the value of illegally mined ore exported from 2006 to 2011, calculated using average international prices. The report documented multiple grave violations by mining companies and government agencies alike: mining outside lease boundaries, excessive extraction beyond permissible limits, evasion of royalties, and outright illegal mining in areas with no valid lease. It accused various authorities of turning a blind eye to – or in some cases facilitating – the rampant illegalities. Crucially, the report squarely indicted Goa’s political leadership: the then Chief Minister (Digambar Kamat, who had also been the mining minister for a decade) was named for permitting the plunder of Goa’s natural resources.

Public outrage in Goa was immediate. Within days, the state government (led by a new Chief Minister, Manohar Parrikar) announced a suspension of all mining in Goa on September 10, 2012. The central Ministry of Environment & Forests likewise withdrew environmental clearances for mines, effectively halting any legal mining activity. Subsequently, on October 5, 2012, the Supreme Court of India stepped in by issuing an order restraining all mining and transportation of iron ore in Goa until further notice (The State of Mining in Goa | Goa Foundation : Goa Foundation). This was an interim measure as the Supreme Court admitted a PIL (Writ Petition No. 435/2012) filed by the environmental NGO Goa Foundation based on the Shah Commission’s findings. For the first time in Goa’s history, iron ore mining came to a complete standstill. The suspension brought instant relief to the environment – rivers ran reddish-brown with silt no more – but it also caused economic pain in Goa. The Shah Commission had recommended strict action: prosecution of offenders, recovery of the losses, and environmental restoration. As Goa awaited the final verdict from the Supreme Court, it was clear that the unbridled party of the China boom was over, and a new paradigm of accountability was about to begin.

The 2014 Supreme Court Judgment (Goa Foundation Case)

After months of hearings, the Supreme Court delivered its landmark judgment in the Goa mining case on 21 April 2014. This judgment – often referred to as Goa Foundation I – fundamentally reshaped the industry. The Court’s verdict validated many of the Shah Commission’s conclusions and introduced sweeping changes:

All mining after 22 November 2007 was declared illegal: The Court found that all iron ore mining leases in Goa had expired on 22 November 2007 (twenty years after the 1987 abolition of concessions). No valid renewals had been granted by that date. Therefore, any mining activity carried out from November 2007 until the 2012 ban lacked a legal lease and was deemed illegal. This meant every tonne of ore extracted in that period was technically without authority, opening the door for the state to recover the value of that ore from the companies. The ruling, in essence, wiped the slate clean – all existing mining leases were nullified for having expired.

Cap on future extraction: Concerned about environmental sustainability, the Supreme Court imposed an interim cap of 20 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) on iron ore that could be mined in Goa. This was roughly half of the peak output during the boom. The Court appointed an Expert Committee to conduct a detailed study and recommend a scientific annual cap for sustainable mining in Goa. Until then, 20 mtpa would be the upper limit.

Handling of mining dumps: The judgment noted the presence of large waste dumps (piles of low-grade ore and soil) across Goa’s mining belt. An estimated 700 million tonnes of mining rejects were piled in and around lease areas. The Court directed the Expert Committee to examine and recommend how to deal with these iron ore dumps. In some cases, dumps on public land (outside lease boundaries) could be confiscated and the material sold for the state’s benefit under strict supervision.

E-auction of extracted ore: To prevent mined ore from being siphoned off or sold illicitly during the ban, the Supreme Court set up a Monitoring Committee to oversee e-auctions of all the iron ore already mined and lying in stockpiles. Roughly 15 million tonnes of ore were in stock at pits, jetties, and transit when mining was halted. The Court ordered that this inventory be sold via public e-auctions under the committee’s supervision, with the proceeds to be deposited with the state (minus a portion payable to leaseholders to cover basic costs).

Goa Iron Ore Permanent Fund: In a first-of-its-kind move in India, the Supreme Court directed the creation of a Goa Iron Ore Permanent Fund as a means of safeguarding part of the mineral wealth for future generations. The Court ordered that from now on, 10% of the sale value of all iron ore extracted in Goa would be deposited into this Permanent Fund. Such a fund, the Court noted, would operate similar to a sovereign wealth fund – investing the proceeds for the long-term benefit of Goans. This was a pioneering judicial step to ensure sustainable development.

Overall, the April 2014 judgment was a watershed. It not only cracked down on past illegality by “resetting” the industry to zero but also laid down new guidelines for any revival of mining with far greater oversight. The immediate impact was that mining remained suspended even after the judgment – until the state could organize a proper system to resume operations within the Court’s framework. Another consequence was the question of liability and recovery, as the Court implied that authorities should demand that mining companies pay back the profits from the post-2007 illegality. By mid-2014, Goa’s iron ore industry was at a standstill – but there was a path laid out for its revival under stricter conditions.

Resumption and Second Shutdown (2015–2018)

After the 2014 Supreme Court judgment, responsibility shifted to the Goa government to chart a path forward. Mining could theoretically resume, but only under new legally valid leases and with environmental clearances, all within the 20 MT annual cap. At this juncture, the Goa government faced a choice: auction the mining leases to new bidders or renew the leases of the old leaseholders. In 2014, the Indian Parliament was also amending the national mining law to mandate auctions. The state government, eager to restart mining quickly, leaned toward reinstating the previous leaseholders.

By late 2014, the Goa government (led by Chief Minister Laxmikant Parsekar) began processing “second renewal” applications of those 88 mining leases that had existed pre-ban. In a hurried spree between November 2014 and January 2015, lease after lease was renewed in favor of the same companies that held them earlier. The haste was extraordinary – 56 leases were renewed within a week (Jan 5 to Jan 12, 2015), with 31 leases renewed on a single day: 12 January 2015. By pushing through the renewals just before the new auction requirement came into effect on January 12, 2015, the Goa government effectively bypassed the mandate. Critics saw it as a blatant attempt to favor incumbent mining companies over the public interest.

With the renewals in hand, mining companies moved to restart operations. By late 2015 and early 2016, iron ore extraction in Goa gradually resumed on a small scale. The years 2015–2017 saw a cautious comeback, operating under new monitoring mechanisms. However, the renewals were soon challenged by the Goa Foundation, which argued that the state should have conducted auctions rather than gifting 20-year extensions to the same operators accused of past misconduct.

On 7 February 2018, the Supreme Court quashed all 88 mining lease renewals granted in 2014–15, terming them “unduly hasty,” arbitrary, and in violation of law. It concluded that no mining could take place on these leases until they were granted afresh in accordance with law. The Court allowed mining activity only until 15 March 2018 to wind up operations, after which all mining in Goa was ordered to stop again from 16 March 2018. This marked the second complete shutdown of Goa’s mining industry in a decade.

Fallout of Lease Quashing: Lokayukta Inquiry and Accountability

The Supreme Court’s 2018 judgment not only halted mining but also cast doubt on the integrity of the decision-makers who had rushed through the lease renewals. The Goa Foundation took the battle to the state’s anti-corruption ombudsman, the Goa Lokayukta, alleging that the manner in which the 88 leases were renewed was an act of corruption. The complaint named former Chief Minister Laxmikant Parsekar, along with the then Secretary for Mines and the Director of Mines, as responsible for decisions that caused a huge loss to the state exchequer by not auctioning the leases.

After investigating, the Lokayukta, Justice P.K. Misra, delivered a scathing report in 2019. He concluded that the second renewal of the mining leases in Goa appeared to be the result of corrupt practices and an abuse of power. By renewing 56 leases in the span of 7 days, officials had clearly attempted to avoid the auction route. In his report, the Lokayukta stated that the three respondents abused their official position, thereby causing loss to the entire State of Goa and benefitting only a few mining lease holders. He recommended that an FIR be filed to initiate a criminal investigation under the Prevention of Corruption Act, and that it be handed over to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). So far, however, no high-profile prosecution has been reported.

In parallel, other efforts at accountability were underway. A Special Investigation Team (SIT) of the Goa Police had been set up back in 2013 to investigate dozens of cases of illegal mining. Over the years, the SIT filed multiple charge sheets, but progress was slow. By 2022, it was reported that the SIT had achieved little in terms of convictions, with most cases still mired in procedural delays or closed quietly. This underscored the challenges in pursuing criminal accountability for the complex, decade-spanning mining scam.

Further Litigation and Policy Debates (2018–2022)

With mining idled again after March 2018, the focus shifted to how (and if) the industry could be revived legally. Litigation and policy discussions ensued:

• Review Petitions in Supreme Court: The Goa state government and Vedanta both filed review petitions against the Supreme Court’s February 2018 decision, requesting the Court to reconsider. However, both petitions were filed far beyond the usual 30-day limit. In July 2021, the Supreme Court dismissed the pleas due to excessive delay and lack of justification.

• Vedanta’s “50-year lease” Argument: Vedanta argued that a 2015 amendment to the Mines and Minerals (Development & Regulation) Act (MMDR Act) granting mineral leases 50-year terms should apply retroactively to Goa. The Supreme Court rejected this plea in September 2021, affirming that auctions were the correct route.

• Legislative and Executive efforts: The Goa government explored legislative fixes to restart mining, seeking possible exemptions due to economic distress. Ultimately, lawmakers acknowledged that competitive bidding (auctions) was the only viable path forward.

• Economic impact and interim relief: The mining ban’s economic impact on Goa was significant. State revenues from mining royalties dropped sharply, allied businesses suffered, and unemployment climbed in mining areas. The state provided some temporary assistance to affected communities, but the industry largely remained at a standstill.

By 2022, it became clear that fresh leases via auction were inevitable to restart Goa’s mines. This signaled a shift away from the old Portuguese-era concessions and renewed leases.

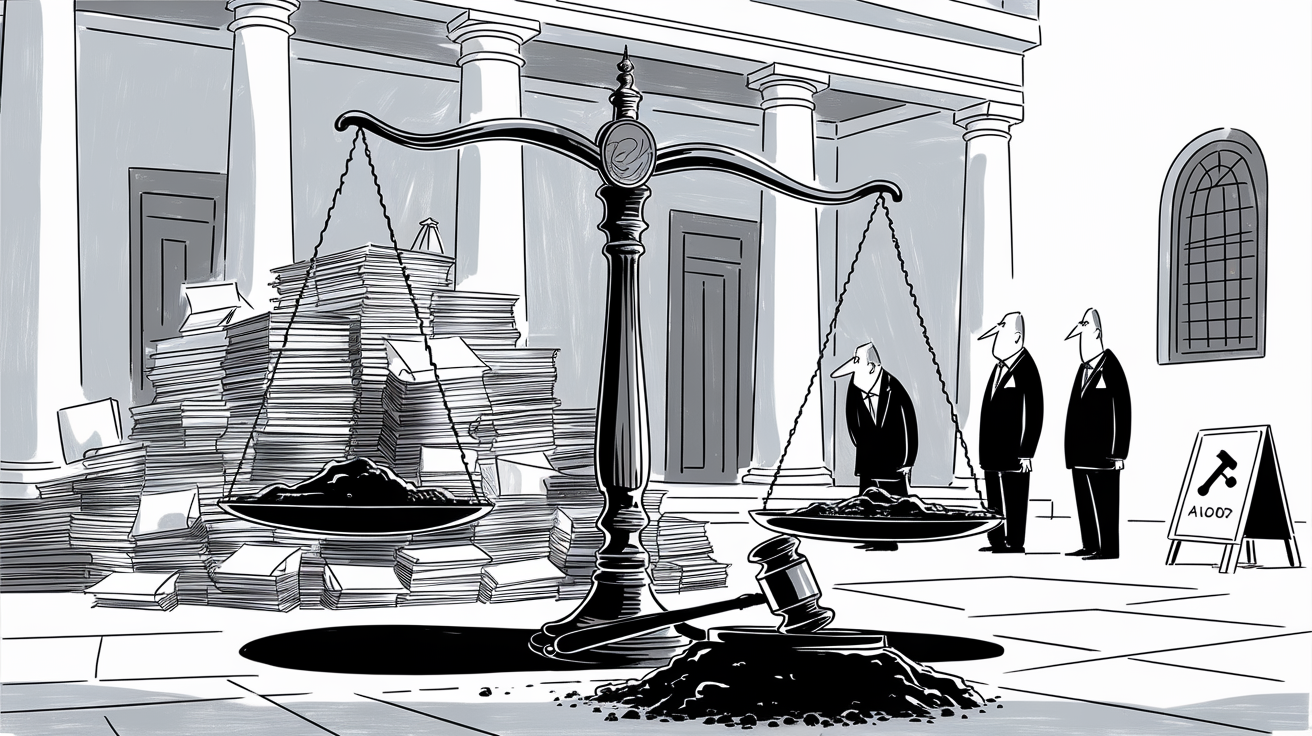

Auctions and the Road Ahead (2022–Onwards)

Having exhausted legal challenges, Goa finally embraced the auction route to restart its mining industry. In 2022, the state government, with central assistance, prepared to auction iron ore blocks to new operators. The first phase of mineral lease auctions was launched in late 2022. Four iron ore blocks were successfully auctioned, corresponding to several former concession areas merged into larger blocks:

- Vedanta Ltd won the Bicholim-Mulgao block in North Goa, with over 84 million tonnes of iron ore reserves.

- Salgaocar Shipping Co. Pvt Ltd won the Sirigao-Mayem block in North Goa, with about 24 million tonnes of reserves.

- Rajaram Bandekar Pvt Ltd (R.B. Mines) won the Monte de Sirigao block in North Goa, containing around 10 million tonnes.

- Sociedade de Fomento Industries Pvt Ltd (Fomento) secured the Kalay block in South Goa, with approximately 16.7 million tonnes of reserves.

These auctions promised to maximize revenue for the state through competitive bids and to introduce transparency in a sector previously plagued by favoritism. With new leases in place, the government projected that mining operations could restart by early 2024, once environmental clearances and licenses were obtained. Meanwhile, oversight remains crucial to avoid repeating past mistakes. The Supreme Court’s directives, including the Permanent Fund requirement, remain in effect, and Goa must address large legacy issues such as waste dump management and environmental restoration.

In conclusion, the story of iron ore mining in Goa is a cautionary tale of boom and bust. From the modest beginnings of the early 20th century, through the Portuguese expansion and post-liberation transitions, to the China-driven surge and subsequent legal shutdowns, mining has brought both prosperity and peril to Goa. The legal interventions since 2012 were a response to the excesses and a call for sustainable governance of natural resources. As of 2025, Goa stands at the threshold of restarting its mining industry under a new paradigm of auctions and stricter oversight. If the mistakes of the past are addressed, Goa’s mining can perhaps become a model of balanced resource management, contributing to the economy while preserving the environment and the interests of future generations.

References

- Alvares, C. & Basu, R. (2022). The State of Mining in Goa. Goa Foundation. (Discusses the history and legal battles surrounding Goa’s mining industry) The State of Mining in Goa | Goa Foundation : Goa Foundation

- Goenchi Mati Movement (2016). The Great Goan Mining Heist: Implications of the 2014 Supreme Court Judgement Ruling. (Analysis of mining losses and the impact of the Supreme Court’s 2014 judgment) The Great Goan Mining Heist: Implications of the 2014 Supreme Court Judgement Ruling – The Goenchi Mati Movement

- Hindustan Times (2012). Goa mining scam worth Rs 34,935 crore: Justice Shah Commission. (Summary of Shah Commission findings) Goa mining scam worth Rs 34,935 crore: Justice Shah Commission | Latest News India - Hindustan Times

- Hindustan Times (2021). SC rejects Goa govt, Vedanta pleas to review judgment cancelling mining leases. (Supreme Court’s dismissal of review petitions) SC rejects Goa govt, Vedanta pleas to review judgement cancelling mining leases - Hindustan Times

- Times of India (2013). Portugal turns to mining to boost economy. (Historical context on mining in Goa during the Portuguese era) Portuguese Authorities In Goa: Portugal turns to mining to boost economy | Goa News - Times of India

- Times of India (2024). Ten years later, SIT probing 35k cr mining scam has nothing to show. (Progress report on the Special Investigation Team)

- Times of India (2019). File FIR against Laxmikant Parsekar, bureaucrats for mining renewals. (Coverage of Goa Lokayukta’s indictment of officials for lease renewals)

- Economic Times (2022). Goa government completes first phase of auction of iron ore mining blocks. (Details on the 2022 auctions) Goa government completes first phase of auction of iron ore mining blocks

- CUTS International (2022). Policy Brief: Suspending Iron Ore Mining in the State of Goa. (Overview of the economic impact of mining suspension)

- Goa Mineral Ore Exporters’ Association (2018). History Timeline of Mining in Goa. (Chronology of mining in Goa) History Timeline