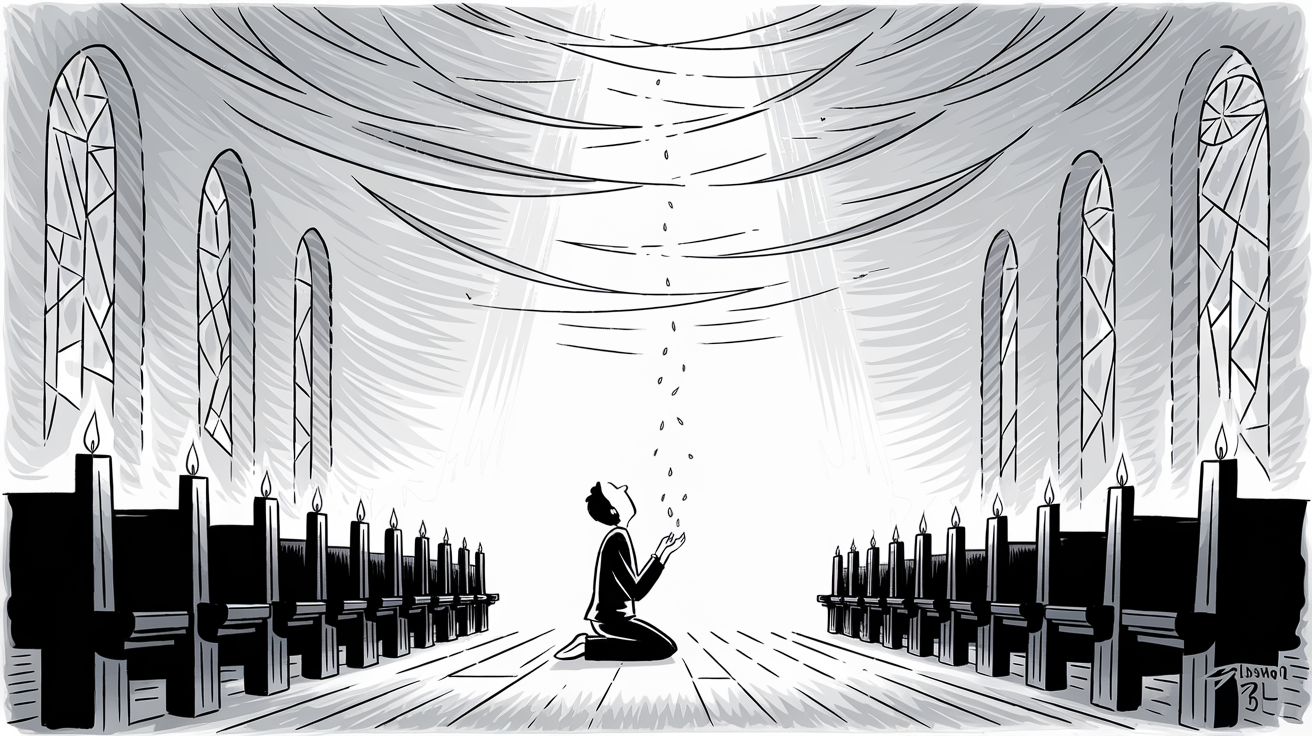

God as "Random Seed": Mystery and Uncertainty in Catholic and Christian Thought

The metaphor of God as the "random seed" – an unknowable, unpredictable core of reality – resonates with a longstanding Christian intuition that God is ultimate Mystery, beyond full human understanding. Catholic theology in particular emphasizes that God's nature eludes complete comprehension, and it invites the faithful to trust in God's providence even amid uncertainty. In what follows, we explore how this idea of a divinely "unknowable randomness" aligns with Catholic and broader Christian thought. We will consider the Catholic understanding of God's mysterious nature, the role of faith and uncertainty in the life of believers, insights from theologians and Church Fathers on chance and free will in creation, scriptural encouragement to embrace the unknown in trust, and the witness of mystical/apophatic theology that God is beyond rational grasp.

Divine Mystery and God's Unknowability in Catholic Thought

Christian tradition has always taught that God's essence is ultimately beyond the reach of human reason. In Catholic theology, God is infinitely transcendent – meaning no human concept or description can fully capture who God is (Catechism of the Catholic Church | Catholic Culture). The Catechism of the Catholic Church explicitly states: "Even when he reveals himself, God remains a mystery beyond words: 'If you understood him, it would not be God.'" Here the Catechism quotes St. Augustine, who cautioned that any god we think we have fully grasped in our minds is not the true God. In Augustine's words, "If you think you have grasped him, it is not God you have grasped." This captures the Catholic conviction that God by nature exceeds our intellectual limits – an idea closely aligned with viewing God as an "unknowable" source at the core of all that exists.

Catholic doctrine has long used the term "mystery" to describe truths about God that surpass human reason. A mystery in theology does not mean a solvable puzzle, but a reality so deep we can never exhaust it. For example, the Trinity is called the central mystery of Christian faith – not fully explicable by logic alone. The First Vatican Council taught that there are real divine mysteries which human reason, on its own, could never discover or prove; anyone denying this was corrected by the Church. Thus, Catholic faith openly acknowledges that God's nature and will are only partially revealed to us, and much remains hidden. As the Bible exclaims, "How unsearchable are His judgments and how inscrutable His ways!" (Romans 11:33) – underscoring that an element of holy unknowability is intrinsic to God. This aligns well with the notion of God as a "random seed" at the heart of existence: a source of being that is fundamentally inscrutable and unpredictable to the created mind.

Faith, Uncertainty, and Trust in Divine Providence

Because God is beyond full comprehension, faith for Christians necessarily involves accepting uncertainty and trusting God's wisdom. Far from requiring absolute logical certainty, Catholic teaching sees faith as a virtuous leap into the unknown guided by confidence in God's character. As one Catholic reflection puts it, "we are invited to embrace the mystery of God and to approach the unknown with both humility and trust", recognizing that acknowledging the limits of our knowledge is not a weakness but a doorway to deeper faith. This humility before the mysterious God is the beginning of true wisdom: "The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom" (Prov. 9:10) – meaning a reverent awareness of God's greatness and our own finitude.

Scripture and tradition repeatedly teach believers to live by faith rather than by sight. St. Paul famously wrote, "For we walk by faith, not by sight" (2 Corinthians 5:7), highlighting that we orient our lives by trust in God's promises, not by visible certainties. Likewise, the Letter to the Hebrews defines faith as "the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction of things not seen" (Hebrews 11:1). This implies that uncertainty is an inherent part of faith – we do not see everything clearly, yet we confidently entrust ourselves to God. Biblical heroes exemplify this "trust amid the unknown": Abraham ventured into a new land on God's word, "not knowing where he was to go" (Heb 11:8); the Virgin Mary said "yes" to God's plan despite not grasping all its details (Luke 1:34-38); and Job, amid his suffering, admitted human ignorance before God's vast purposes: "I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know" (Job 42:3). In each case, faith meant trusting God's providence without having all the answers.

Catholic philosophy and theology underscore that such trust is rational in its own way, even if it goes beyond strict proof. Acknowledging uncertainty is seen as part of a healthy faith and reason relationship. Pope St. John Paul II taught that human reason must remain humble and open to God – "As a theological virtue, faith liberates reason from presumption", freeing us from the arrogance of thinking we can know everything. In other words, faith "teaches reason humility" by recognizing a transcendent realm beyond human mastery. This humble stance allows one to trust in God's providence. The attitude of "I don't have to know everything, because I know God" is fundamental to Christian life. The 5th-century bishop St. Augustine put it succinctly: "Trust the past to the mercy of God, the present to His love, and the future to His providence." In practice, Catholics structure their lives around prayer, sacraments, and moral commitments that assume God's faithful guidance, even when outcomes are uncertain. Rather than being paralyzed by the unpredictability at the core of existence, believers find security in God's character – His goodness and wisdom – and thus can move forward without knowing every detail of the plan.

Providence, Free Will, and Apparent Randomness in Creation

Christian thinkers have long wrestled with how chance and randomness in the world relate to God's plan. The consensus in Catholic theology is that what appears random or accidental to us is still encompassed within divine providence. The Church Fathers and theologians taught that no event escapes God's knowledge and will, yet God can work through contingent, unpredictable processes. For example, St. Augustine argued that nothing truly happens by pure chance; if something seems random, it is only because we do not see the full causes at work. He writes that what people call "fortune" is in fact governed by "a certain hidden order" arranged by God – "What we call a matter of chance may be only something whose why and wherefore are concealed". In Augustine's view, the universe has an order known to God alone, so what looks like chaos or luck from a human perspective is ultimately woven into a purposeful divine design.

Later, St. Thomas Aquinas offered a nuanced explanation reconciling divine providence with real contingency (chance) in nature. Aquinas taught that God is the First Cause of all that happens, but He operates through different kinds of secondary causes. Some things God wills to happen necessarily (following fixed laws), and other things He wills to happen contingently (by freedom or chance). "The effect of divine providence is not only that things should happen somehow, but that they should happen either by necessity or by contingency," Aquinas explains. In other words, God's plan deliberately includes both certainty and randomness. "Whatsoever divine providence ordains to happen infallibly and of necessity, happens infallibly and of necessity; and that happens from contingency, which the plan of divine providence conceives to happen from contingency." God no more overrides genuine randomness than He overrides genuine human free will – both are real features of creation, given by the Creator. According to Aquinas, the universe is richer and more "perfect" for containing this interplay of necessity and chance. Thus, Catholic thought holds that divine providence does not eliminate randomness; rather, God is wise enough to work through randomness to accomplish His purposes. Even modern Catholic theologians affirm that "true contingency in the created order is not incompatible with a purposeful divine providence" – any random process can still fall within God's plan, since "divine causality can be active in a process that is both contingent and guided."

One practical consequence of this view is the reconciliation of free will with God's sovereignty. Human free will introduces genuine uncertainty into the world – each person can choose good or evil. Yet this freedom is God-given and God foresaw all possible outcomes. Catholics believe God's providence is so masterful that it encompasses our free choices without negating them. This means the course of history is not rigidly predetermined; from our angle it unfolds with openness and surprise, but from God's angle it unfolds exactly as He permits and knows. The Bible hints at this paradox in Proverbs 16:33: "The lot is cast into the lap, but its every decision is from the Lord." What looks like a random dice-roll is under divine supervision. In sum, while Christians would not say "God is random," they do affirm that God is behind all the spontaneity and chance that we experience, the ultimate "random seed" underpinning a world of both order and surprise. The world is not a meaningless roll of the dice; it is guided by an inscrutable providence, wherein God "carries all things by his wisdom and love" even when we cannot discern the pattern.

Embracing Mystery: Scripture and Tradition on Faith amid Uncertainty

Both Scripture and Church tradition encourage believers to embrace divine mystery with faith-filled confidence. The New Testament acknowledges that in this life we do not have direct sight of God's full reality: "Now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then face to face" (1 Corinthians 13:12). Therefore, Christians are called to live in hope and trust until the day when things become clear. Jesus Himself praised those who believe without needing total proof: "Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe" (John 20:29). Rather than demanding exhaustive knowledge, God asks for trust – much as a child trusts a loving father. This theme of trusting God's providence runs throughout Scripture. "Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not rely on your own insight," says Proverbs 3:5-6, promising that God "will make straight your paths." Jesus taught His disciples not to be anxious about the uncertainties of tomorrow, because the Father knows their needs (Matthew 6:25-34). In essence, the Bible invites us to surrender control and lean on the wisdom of the "unknowable" God, assured that He is faithful.

Catholic tradition has reinforced this biblical message. The lives of the saints often illustrate profound trust amid ambiguity. For instance, St. Therese of Lisieux spoke of her spiritual way as a "little path" of childlike trust, even when she felt darkness or silence from God. St. John of the Cross, a 16th-century mystic, wrote about the "dark night of the soul" – times when one's understanding is in darkness, yet the soul is being led by God's unseen hand. John taught that faith itself is a kind of darkness to the intellect – we believe what we cannot yet see. In the Dark Night he says God purges our reliance on feelings and ideas, bringing us to a "luminous darkness" where we travel purely by trust in God. This echoes the apostolic teaching that "we walk by faith, not by sight." Rather than this being a handicap, Christians regard it as an opportunity for love: to love God for who He is, above and beyond the gifts or signs we might receive. Faith is a commitment to a Person (God), not a formula – thus uncertainty can coexist with deep personal confidence. As Catholic author Flannery O'Connor once noted, "faith is what someone knows to be true, whether they believe it or not" – a paradoxical way of saying faith is a mode of knowing that doesn't rely on empirical proof, but on trust in God's truthfulness. In Catholic understanding, then, embracing holy uncertainty is part of structuring one's life around God. We obey moral laws, pursue vocations like marriage or religious life, and endure trials without knowing exactly how it all works out, because we trust the Mystery who has promised to be with us. This faithful venture is summed up well by the Second Vatican Council, which taught that only in God does man find the light and strength to navigate life's ambiguities; without God, "the mystery of human life" remains unsolved. In short, both Scripture and Catholic tradition affirm that not-knowing in full is an essential ingredient of a vibrant faith, keeping us humble and open before the transcendent God.

Mystical and Apophatic Theology: God Beyond Rational Comprehension

Perhaps the strand of Christian thought most akin to the idea of God as an "unknowable core" is apophatic theology, also known as "negative theology," and the heritage of Christian mysticism. Apophatic theology emphasizes what cannot be said about God, insisting that God transcends all our categories. From the earliest centuries, Christian mystics have described encountering God as darkness or silence – not because God is absent, but because He is beyond the capacity of human concepts. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a 5th-century theologian whose works deeply influenced Catholic mysticism, taught that the highest truth about God is reached not by knowing but by "unknowing." He writes that "no finite knowledge can fully know the Infinite One, and therefore He is only truly to be approached by agnosia – by that which is beyond and above knowledge." In Dionysius's view, to grasp God we must go beyond all our positive descriptions into a cloud of unknowing. He even calls God the "Nameless" and "the beyond-being" to stress that our minds literally cannot pin God down. This apophatic emphasis is strongly reflected in Eastern Christianity and also in Western Catholic mystics.

A classic medieval Catholic mystical text, The Cloud of Unknowing (14th century), directly counsels the believer to give up trying to comprehend God with the intellect. "Let us abandon everything within the scope of our thoughts and determine to love what is beyond comprehension," the Cloud author advises. He describes how in contemplative prayer one seeks God in a "cloud of unknowing," a dark mist before the intellect. No matter how much we think or reason, "None of your efforts will remove the cloud that obscures God from your understanding." Rather, "Our minds will never grasp God by thinking." The only way to "touch" God is by love and surrender, not by analysis. This theme – that God is met in darkness or unknowing – is echoed by saints like St. Gregory of Nyssa (who spoke of Moses meeting God in the "darkness" on Sinai) and St. John of the Cross (who said that in the darkness of faith the soul is united to God). Such mystical theology aligns with the idea of God as the ultimate ineffable foundation of reality. It affirms that if you probe to the very core of existence, you encounter not a clear formula, but an infinite Mystery – a "randomness" only in the sense that God cannot be predicted or controlled by creaturely logic. As one modern commentator summarized the apophatic insight: "God can be loved, but not thought."

Importantly, this does not mean God is disorderly or irrational; rather, God is trans-rational – beyond the limits of created reason. Catholic mystics maintain a profound sense of God's order and goodness, even as they confess His unknowability. In apophatic prayer, the soul trusts that even though it cannot understand God, it is safe in God's presence. This mirrors the "random seed" idea by suggesting the ground of being is something fundamentally opaque to intellect yet fertile with all possibilities. Just as a random seed in computing generates unpredictable outcomes, God as the divine "seed" of reality gives rise to a creation filled with contingency and surprise, all rooted in His unfathomable freedom. Catholic mysticism ultimately finds peace in this truth: God is mystery, and that is a cause for wonder and worship, not frustration. As the 4th-century theologian St. Gregory Nazianzen wrote, "God is infinite and incomprehensible; all that is comprehensible about Him is His infinitude and incomprehensibility." The appropriate response, then, is to adore the mystery. This attitude upholds that seeing God as the unknowable core of existence is not only compatible with Christian thought, it is at the very heart of a rich tradition of apophatic theology and mystical spirituality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the notion of God as an inscrutable "random seed" at the core of reality finds strong resonance in Catholic and broader Christian thought. Christianity proclaims that God's essence is a sacred mystery, forever beyond full human grasp. Believers are invited to trust and love this mysterious God, structuring their lives around faith even without complete understanding. Classical theology insists that uncertainty and contingency in the world do not conflict with God's providence – rather, they are part of His design, which our minds cannot wholly trace. The freedom of God and the freedom He grants creation mean that from our viewpoint there is genuine randomness, though from God's vantage point there is an intelligible (if hidden) order. Scripture and tradition consistently teach us to embrace the unknown with faith and humility, echoing the idea that at the heart of existence is an unseen foundation we rely on (Acts 17:28: "in Him we live and move and have our being"). Finally, the rich vein of Catholic mysticism and apophatic theology celebrates God's transcendent unpredictability, inviting us into the "cloud of unknowing" where we encounter the Divine on its own terms. In Christian understanding, therefore, calling God the "random seed" of reality is a poetic way to acknowledge that God is the ultimate source who cannot be fully figured out – a God who exceeds all formulas, yet who undergirds and guides everything with purpose. This inspires not despair, but a reverent confidence: "Though we cannot see the whole path, we know the One who lights each step." The faithful can rest assured that the mystery at the core of existence is not chaotic meaninglessness, but the presence of the living God – infinitely wise, infinitely free, and infinitely loving.

Sources:

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, on God's mystery (Catechism of the Catholic Church | Catholic Culture)

- St. Augustine, Sermon 52 and 117, on God's incomprehensibility

- Catholic Answers (Mark J. Giszczak), "When You Just Don't Know," on embracing mystery with humility (When You Just Don't Know | Catholic Answers Magazine)

- St. Augustine, Contra Academicos I.1, on providence and so-called chance

- St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I, q.22, a.4, on divine providence and contingency (SUMMA THEOLOGIAE: The providence of God (Prima Pars, Q. 22))

- International Theological Commission, Communion and Stewardship (2004), §69, on God's providence and random natural processes (Communion and Stewardship: Human Persons Created in the Image of God)

- The Cloud of Unknowing (14th c.), on loving God beyond comprehension

- Pseudo-Dionysius, Mystical Theology, on "unknowing" God (Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite Quotes)