Controlling Resources vs. Market Reliance: Why Companies Acquire for Control

Companies often prioritize control over critical resources by acquiring suppliers, distributors, or firms with key capabilities, rather than relying on open market transactions. This strategic choice - exemplified by vertical integration or resource-driven mergers - raises the question: do firms simply mistrust market forces, or are there deeper economic and strategic reasons? Multiple factors drive companies to internalize resources, including transaction cost efficiencies, risk management, competitive advantage, and shareholder pressures. This analysis explores the economic theories behind "make or buy" decisions, real-world business strategies, and case studies illustrating why control is favored. It also examines the trade-offs between maintaining control and leveraging market dynamics, showing that choosing to acquire vs. contract is a balance of costs, risks, and benefits.

Economic Theories Explaining the Preference for Control

Several classic economic theories shed light on why firms expand their boundaries to control resources instead of transacting in markets:

Transaction Cost Economics (Coase & Williamson): Economist Ronald Coase noted that using the market is not free - there are transaction costs (searching for suppliers, negotiating contracts, enforcing agreements, etc.) Coase: "The Nature of the Firm". When these market costs are high, it can be more efficient to perform the activity in-house or by owning the supplier. In Coase's words, "Firms exist to economize on the cost of coordinating economic activity", eliminating the need for constant price negotiations. Oliver Williamson later added that if a transaction involves uncertainty, asset specificity, and potential opportunism, markets may "fail" and lead to a hold-up problem (one party exploiting the other). In such cases, integrating (through acquisition) safeguards the firm. Indeed, studies show vertical integration reduces exposure to opportunistic supplier behavior, albeit at the cost of high investment and reduced flexibility (Revista ESPACIOS | Vol. 37 (No. 01) Ano 2016) and When and when not to vertically integrate | McKinsey. In short, if contracting externally is too risky or expensive, firms expand their boundaries to gain control.

Resource Dependence and Uncertainty: Beyond pure cost calculations, companies fear being too dependent on external entities for vital inputs. Resource dependence theory (Pfeffer & Salancik) argues that firms seek to minimize external dependencies that can threaten their survival. By acquiring suppliers or critical resource owners, a company reduces uncertainty in supply, insulating itself from market fluctuations or power imbalances. An integrated firm can ensure a steady flow of needed materials and information, rather than hoping the market will deliver (Vertical Integration: Definition, Examples, and Advantages - Inbound Logistics). For example, if a manufacturer relies on a sole supplier for a key component, it faces major uncertainty - the supplier could raise prices or fail to deliver. Bringing that supplier in-house (via acquisition) guarantees supply and mitigates that risk. Thus, it is not mere "mistrust" of markets, but a rational response to uncertainty and dependency.

Resource-Based View (RBV): The RBV in strategic management emphasizes owning unique resources as a path to sustained competitive advantage (Resource-based view - Wikipedia). If a particular resource or capability is valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN), firms have strong incentives to internalize it. Acquiring a company with proprietary technology, talent, or raw material reserves can secure these advantages exclusively. In effect, the firm turns an external resource into an internal strength that competitors cannot access. This explains many tech acquisitions: companies buy startups to obtain valuable intellectual property or expertise rather than licensing or sharing it. The underlying logic is that controlling strategic assets yields greater long-term value than relying on market contracts that others can also tap.

In summary, economic theory suggests that firms expand via acquisitions when market transactions are comparatively costly or risky. It is not always about "mistrusting" the market's invisible hand in principle - it is about calculating when internal control will be more efficient or secure than arms-length deals. Next, we consider specific strategic motives and examples that align with these theories.

Strategic Drivers for Acquiring Control over Resources

Building on those theories, companies have practical strategic reasons to favor control through acquisitions. Key drivers include risk mitigation, securing competitive advantages, and meeting stakeholder expectations:

Supply Security and Risk Management: One major motive is to reduce supply chain risks. Vertical integration (acquiring suppliers or distributors) can "mitigate the risk of supply chain disruptions and price volatility" by ensuring a steady in-house supply. For instance, during industry-wide shortages or geopolitical uncertainty, an integrated firm can rely on its captive supplier instead of scrambling on the open market. A contemporary example is how some automakers responded to semiconductor shortages - rather than depend solely on external chip vendors, companies like Tesla leveraged in-house software tweaks and considered integrating more chip design to avoid bottlenecks (Tesla's vertical integration and preparation were keys to avoiding ...). By owning critical inputs, firms avoid being at the mercy of market swings or a powerful supplier. This is essentially a hedge against risk: the firm trades the uncertain market price for the more controllable (though fixed) costs of running an acquired supply unit.

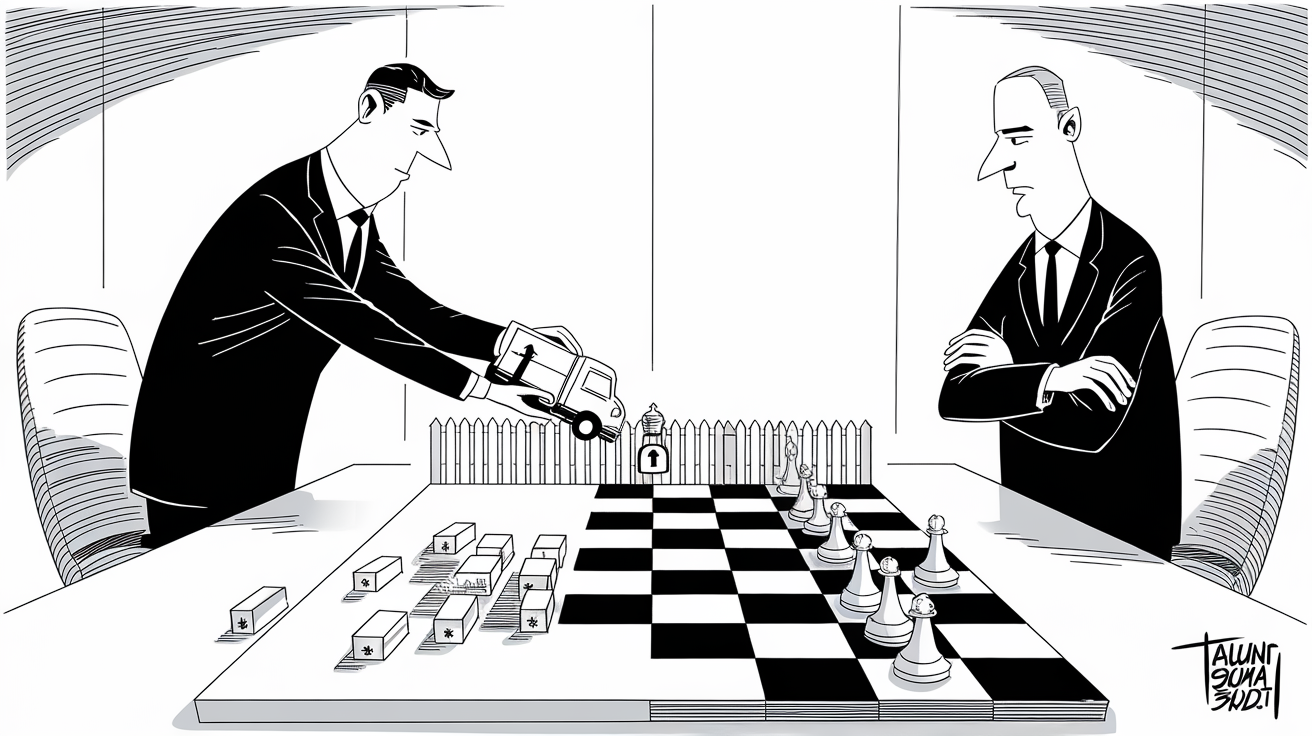

Avoiding Supplier Market Power (and Opportunism): When upstream or downstream players have excessive market power, companies may acquire them to level the playing field. A striking case comes from the Australian ready-mix concrete industry. Ready-mix producers faced high input costs because a few quarry companies controlled the supply of sand and stone and were charging monopoly-like prices. In response, the concrete firms backward integrated via acquisitions, taking control of quarries - today, three players control about 75% of both concrete production and quarries. This move was driven by a mistrust of being price-gouged: in one region "the few players [in quarries] charged prices well above competitive levels... therefore, the concrete companies integrated into quarries via acquisitions." By doing so, they eliminated the supplier's leverage. However, this strategy can backfire if the acquisition price fully capitalizes the supplier's high margins (paying a steep premium). Indeed, some of those quarry acquisitions likely destroyed value by overpaying, illustrating a trade-off. Nonetheless, the incentive was clear - when a supplier can exploit you, buy the supplier. This logic extends to any situation of vertical market failure: if the market cannot be trusted to set fair prices due to a monopoly or bilateral oligopoly, integration is a defensive move. Companies essentially mistrust specific market conditions (e.g. a sole supplier), not the concept of markets in general.

Competitive Advantage and Differentiation: Owning unique resources can confer a competitive edge that market-sourced resources cannot. A classic example is Apple Inc.'s vertical integration strategy. Apple designs its own chips (after acquiring chip companies and talent), builds proprietary software, and tightly controls hardware manufacturing. This end-to-end control has "allowed Apple to set the pace for mobile computing", enabling innovations like improved battery life that competitors struggle to match (Vertical Integration Works for Apple - But It Won't for Everyone - Knowledge at Wharton). An analyst noted Apple could optimize features "precisely because it controls the parts that make up the iPad... owning core intellectual property (chips, battery chemistry, software)". By contrast, a rival dependent on off-the-shelf components has less ability to optimize. Similarly, Netflix shifted from licensing films to producing its own original content. By doing so, Netflix gained exclusive shows and full control over its content library, reducing reliance on studios that could pull licenses. This exclusivity is a huge competitive advantage in streaming - original hits like "Stranger Things" draw subscribers, and in-house production gives Netflix greater control over its offerings and content strategy (Netflix Marketing Strategy: Decoding Their Streaming Success - Marstudio). In both cases, the pursuit of control is about creating or protecting a unique value proposition. It is not that Apple or Netflix distrust suppliers per se; rather, they cannot achieve their desired product quality or differentiation without controlling those resources. Acquisitions and integration become a means to that strategic end.

Cost Efficiency and Synergies: Often, eliminating intermediaries can cut costs or improve coordination. By merging with a supplier or distributor, a company can capture the margin that the supplier used to earn, achieving lower overall cost per unit (avoiding "double marginalization"). Integration can also yield better coordination along the chain, reducing waste or delays. For example, a vertically integrated manufacturer can schedule production in tandem with its captive parts supplier, optimizing inventory levels and design compatibility. As Investopedia notes, vertical integration often leads to "lower costs, economies of scale, and less reliance on external parties" (What Is Vertical Integration?). The oil industry illustrates this: majors like Shell long ago acquired upstream drilling, midstream transport, and downstream refining assets, achieving cost efficiencies and ensuring a smooth flow from oil well to gas pump. However, chasing cost synergies via acquisition only makes sense up to a point - if external suppliers are highly efficient and competitive, a firm might actually lose efficiency by integrating (because it must then manage what specialists did more cheaply). Managers must weigh whether the added control truly lowers net costs or if they are better off leveraging market competition among suppliers.

Quality Control and Innovation Speed: By controlling more of the value chain, companies can enforce quality standards and accelerate innovation cycles. For instance, when Tesla built its Gigafactory for battery production (a form of partial vertical integration with Panasonic as a partner), it aimed to ensure high-quality, high-volume battery cell supply aligned with its exact specifications. This level of coordination would be harder through simple contracts. Similarly, Apple's control over both hardware and software allowed it to seamlessly introduce new features (like FaceID or custom chips) faster than if it had to negotiate with independent suppliers for each improvement. In fast-paced industries, tight integration can be a way to beat the market's speed, because the company does not have to wait for a supplier to develop something - it can do it internally on its own timeline.

Shareholder Expectations and Growth: Finally, the pressure from shareholders and capital markets can drive resource-control acquisitions. Investors often reward companies that secure their supply chains or acquire new capabilities, seeing it as a reduction of future risk or an expansion of profit opportunities. In some cases, shareholders simply expect growth - and acquisitions offer a quick path to growth (buying new revenue streams or assets). For example, in the tech sector, firms like Google, Amazon, and others have expanded into new areas via acquisition partially because Wall Street values the potential for long-term growth and control of key ecosystems. Wharton experts observed that tech giants face "increasing pressure to keep growth rates up" and thus find "expanding into new areas an attractive proposition". Acquiring a supplier or a company with a critical resource can both secure the business against disruptions and signal to investors that the company is taking proactive steps to strengthen its strategic position. On the flip side, investors also caution against blindly building empires - there is evidence that conglomerates get discounted by the market due to management complexity. So shareholder expectations can cut both ways: they want stability and growth, but they also want efficiency and focus. This dynamic means companies must justify acquisitions of resources with clear value creation logic (e.g. synergies, risk reduction) to keep shareholders on board.

In essence, companies pursue resource-control acquisitions for pragmatic reasons: to ensure supply stability, gain an edge over competitors, improve margins, and satisfy strategic goals or stakeholders. It is often less about an ideological distrust of markets and more about addressing specific market limitations or seizing opportunities that ownership provides.

Case Studies and Examples

Real-world examples highlight how these motives play out and the outcomes of choosing control over open-market reliance:

General Motors and Fisher Body (Hold-Up Problem): A classic historical example is GM's acquisition of Fisher Body in the 1920s. Initially, Fisher Body was an independent supplier making car bodies for GM under contract. As GM grew, Fisher Body had bargaining leverage (it could threaten to hold up GM's production or demand higher prices, given GM's reliance and Fisher's specialized investment in body molds). Concerned about this hold-up risk, GM acquired Fisher Body to bring that critical component in-house. This case became a cornerstone in transaction cost economics: it demonstrated that when a supplier relationship involves asset specificity (specialized tools made for one buyer) and potential opportunism, vertical integration can safeguard the buying firm's interests. The GM-Fisher Body story underscores how risk of opportunistic behavior can drive a firm to control a resource instead of trusting contracts.

Australian Concrete and Quarry Integration: As mentioned earlier, concrete manufacturers in Australia acquired quarry suppliers to control raw materials (sand, gravel) because the quarries were exploiting their essential position. The result was an industry structure where a few integrated firms control both concrete production and inputs, ensuring they are not at the mercy of external quarry owners. This solved the pricing power imbalance, but at a cost - some acquisitions were very expensive. It is a cautionary tale: while integration addressed the mistrust of a supplier cartel, paying too much meant some acquirers sacrificed shareholder value for that control. Thus, the case illustrates both the motive (stop supplier gouging) and the trade-off (the price of freedom might be high).

Apple's Integrated Ecosystem: Apple Inc. provides a contemporary success story of prioritizing control. Over decades, Apple has acquired numerous smaller firms (PA Semiconductor for chips, AuthenTec for fingerprint sensors, etc.) to internalize technologies rather than depend on external vendors. By controlling its chip design (the A-series and M-series chips), Apple achieved performance and efficiency gains that helped differentiate its iPhones and Macs. As Wharton's David Hsu noted, "despite the benefits of specialization, it can make sense to have everything under one roof" - Apple's tight hardware-software integration enabled innovations like longer battery life and optimized device performance. An example on the product level: the integration of custom silicon and software allowed Apple to introduce new features (like advanced power management) which competitors could not easily copy, since those competitors were using off-the-shelf chips available to everyone. Apple's approach shows how vertical integration can yield competitive advantage, validating the resource-based view. However, Apple also illustrates that this path requires massive investment and expertise in areas from chip engineering to retail stores. Not every company can replicate it - indeed, others like Sony attempted similar integration (spanning content, hardware, gaming) and struggled to "make the disparate parts gel." Apple's success is as much about execution as strategy.

Netflix and Original Content: Netflix initially relied on licensing movies and shows from studios. As streaming became more competitive, Netflix faced rising licensing costs and the risk of content providers (like Disney) pulling their hit franchises to start rival services. Netflix's answer was to develop and acquire its own content studios and talent - effectively becoming a producer. By doing so, Netflix reduced its dependence on outside studios. It now controls a library of "Netflix Originals" that it can supply to its platform globally without negotiating rights every few years. This gives Netflix self-reliance: popular originals cannot be yanked away by a third party, and subscriber retention improves because Netflix offers unique content. Analysts noted that by producing content in-house, "Netflix can ensure greater control over its offerings" and tailor content to its audience. This vertical integration into content creation was risky (heavy upfront costs and no guarantee of hits), but it was driven by the strategic need to own a resource (content) that is the lifeblood of its service. The success of shows like House of Cards and Stranger Things vindicated the move, while also raising the competitive bar - now every major streaming firm invests in original content, essentially a vertical integration of distribution and production across the industry.

Automotive Industry - Contrasting Approaches: Car manufacturers historically present a mix of strategies regarding control. Henry Ford in the early 20th century famously pursued extreme vertical integration - the Ford River Rouge Complex took in raw materials (iron ore, rubber) and turned them into finished cars, even owning rubber plantations (Fordlandia) to secure tire supply. This was driven by a desire for independence and cost control in an era when supplier industries were less mature. Decades later, the auto industry learned to balance make-vs-buy. Many Western automakers spun off or outsourced component production to specialized suppliers to reduce costs and focus on core assembly (e.g., Delphi was spun out of GM). In contrast, Japanese automakers like Toyota achieved a middle ground: they did not outright own all suppliers, but they cultivated close, long-term partnerships (the keiretsu system) with a few key vendors. Japanese firms were less vertically integrated into components than Western counterparts, relying on stable relationships with outside suppliers. Why did this work for them? One reason cited is cultural and relational - "opportunism is not as rife in Japanese culture", so trust and cooperation replaced the need for ownership. Toyota, for example, could rely on suppliers for just-in-time delivery without needing to acquire them, because mutual trust and benefit were developed (along with practices like Toyota's support to improve supplier operations). This example shows an alternative to integration: if companies can foster enough trust and alignment with suppliers, the market relationship can be nearly as effective as ownership. It underlines that acquisitions are not the only tool - partnerships, joint ventures, or long-term contracts can also secure resources when properly managed. Still, when trust fails or cannot be established, ownership becomes the fallback.

These case studies illustrate a spectrum from fear-driven acquisitions (e.g., GM-Fisher to avoid hold-up, concrete-quarry to escape supplier monopolies) to opportunity-driven integration (Apple, Netflix to create unique value). In each, the firm weighed the reliability and costs of the market versus the benefits and costs of control. Sometimes integration clearly paid off; other times it introduced new challenges. This leads us to the fundamental trade-offs involved in choosing control vs. market reliance.

Trade-Offs Between Control and Market Reliance

Deciding whether to acquire control of a resource or rely on market transactions involves balancing pros and cons. There is no one-size-fits-all answer - the optimal choice depends on context, as shown above. Key trade-offs include:

Control vs. Flexibility: Greater control through acquisition brings stability but can reduce flexibility. When a company owns a supplier, it commits to that supply source and technology. This can be advantageous for ensuring consistency and long-term planning. However, the firm might become "inflexible" if market conditions change. For example, if a new technology emerges outside, a vertically integrated firm might struggle to adapt if its assets are tied to an older tech. Relying on the market, by contrast, allows a company to switch to new suppliers or materials more easily (you can always sign a new contract if something better appears). Integration is a long-term bet - it sacrifices the option to easily pivot suppliers in exchange for dedicated capability.

Reduced External Risks vs. Internal Burden: By internalizing a resource, firms eliminate certain external risks like supplier opportunism, price hikes, or supply disruptions. But in doing so, they take on internal risks and burdens. The company must now manage that resource or business unit itself, which requires expertise and ongoing investment. Vertical integration demands "heavy upfront capital expenditure" and managerial attention to integrate new operations. If a firm lacks experience in the acquired business, it could introduce inefficiencies. Additionally, owning capacity means the firm bears all the risk of under-utilization - if demand drops, an external contract could be scaled down, but a factory you bought is now your fixed cost to carry. Thus, control can trade an external risk for an internal one. The organizational complexity rises with integration, which can erode some benefits. Empirical evidence shows many mergers fail to deliver promised synergies due to integration difficulties or culture clashes. This is why firms must ensure the benefit (e.g., assured supply, margin capture) outweighs the added overhead.

Cost Savings vs. Capital Costs: Bringing a supplier in-house can cut out the supplier's profit margin, potentially lowering unit costs in the long run. It might also achieve economies of scale if the combined entity optimizes production. Indeed, vertical integration can lead to "long-term cost saving...and minimal supply disruptions". However, acquisitions are expensive - the purchase price plus integration costs can be huge. If a company pays a premium to buy a supplier (especially if the supplier was very profitable), it might take years of operational savings to recoup that cost. There is also the risk of overpaying for the target, which can wipe out value. Furthermore, the company now ties up capital in manufacturing assets that could become obsolete. So the trade-off is: pay a predictable supplier margin over time, or pay a lump sum now to eliminate that margin. The best choice depends on how these costs compare and how certain the future is. If a supplier's margins are exorbitant and likely to remain so, buying them might be justified (if bought at a reasonable price). But if the market is competitive (supplier margins thin) or the future demand is uncertain, staying with market purchases might be more cost-effective.

Focus and Core Competence: Relying on the market lets a firm focus on its core business, leveraging specialized suppliers for non-core activities. This can lead to better performance, as each company in the chain focuses on what it does best. When a firm integrates widely, it can lose focus. Managers now have to worry about multiple stages of production, which can dilute attention from the main value-adding activity. If you "integrate disparate businesses, you become so unfocused that you lose the ability to coordinate", highlighting why conglomerates often trade at a discount. In other words, the managerial complexity can outweigh the benefits of control. Companies must evaluate whether owning a supplier will truly enhance their competitive advantage, or if it will distract them. A trade-off exists between breadth and depth: integration increases breadth of operations, potentially at the expense of depth in any one area. One remedy some firms use is partial integration or quasi-integration (e.g., strategic alliances or minority equity stakes) to get some control without full ownership. This can offer a middle path - aligning incentives with a supplier (through a joint venture or long-term contract) to secure supply, while not absorbing the entire business.

Market Efficiency vs. Market Failure: If markets are working well - many suppliers competing, transparent pricing, standard products - then relying on market mechanisms is usually cheaper and easier. The firm can shop around for the best price and let competition drive efficiency. Here, integration offers little advantage and could even raise costs. However, if there is a market failure (such as monopoly, oligopoly, or highly uncertain environment), the market might deliver poor outcomes (high prices, lack of reliability). In those cases, internalizing can correct that failure. The heavy-machinery example from McKinsey illustrates this nuanced decision: for routine work with many outside suppliers (i.e., a healthy market), outsourcing was better - it was "low risk and had low transaction costs," so they advised closing that part. But for a critical, specialized task where only one external supplier was available (a quasi-monopoly situation), they kept an in-house shop to avoid dependence, since that work was unpredictable and a delay would be extremely costly. This split solution saved cost on common tasks via the market, yet maintained control over a critical resource prone to market failure. The lesson is that the decision can be different for different parts of the business: firms might integrate only where the market fails and outsource where the market works. This hybrid approach seeks to get the best of both worlds - efficiency from competition and stability from control.

In evaluating these trade-offs, companies also consider softer factors like culture and trust (as seen in the Japanese example) and the dynamic evolution of industries. Notably, the benefits of integration can change over time. Early in an industry's life, integration may be beneficial to pioneer processes (as in the early computer industry, everything was once integrated). But as industries mature and commoditize, specialization often wins out because suppliers can provide components more efficiently at scale. The PC industry followed this trajectory: it went from vertical giants (IBM making everything) to a horizontal market where different firms excel at chips, software, drives, etc., coordinated largely by market forces. Thus, the ideal degree of control vs. outsourcing is not static - it shifts with technology, competition, and even global events (e.g., recent supply chain disruptions have swung the pendulum back toward more integration or reshoring in some sectors).

Conclusion

Companies prioritize control over resources through acquisitions not out of blind mistrust in markets, but due to clear-eyed assessments of risk, cost, and strategic advantage. When market forces are unreliable or disadvantageous, firms turn to integration as a solution. Economic theory (Coase's transaction costs, Williamson's opportunism, resource dependence logic) provides the rationale: if doing it inside the firm is more efficient or secure than contracting outside, the firm will expand its boundaries. Business strategy factors - securing supply, gaining unique capabilities, preempting competitors, and meeting growth or stability expectations - drive these decisions in practice. Real-world examples from industrial commodities to high-tech and media show how companies carefully weigh the benefits of control against the costs.

Critically, there are significant trade-offs between control and market reliance. Control can bring stability, coordination, and competitive edge, but it comes with inflexibility, heavy investment, and managerial complexity. Reliance on markets offers flexibility and efficiency through specialization, but can expose a firm to price swings, holdup, or supply risk. The optimal choice lies in finding the right balance - identifying which resources are so strategic or risky that owning them outweighs the downsides, while continuing to leverage market mechanisms for non-critical needs or where markets truly excel.

In effect, successful companies do not simply mistrust market forces; they use market forces where they can, and circumvent them where they must. The decision to acquire for control is a strategic one: a bet that internalizing a resource will create more value (or prevent greater loss) than leaving it to the market. Understanding this balance - and the dynamic nature of industries - is key. Firms that get it right secure crucial advantages and resilience, whereas those that go too far in either direction may face inefficiencies or vulnerabilities. Thus, the art of management is in continuously judging where on the spectrum of control vs. market reliance the firm should be for each facet of its business, and adjusting as conditions change. The ultimate goal is to deliver on shareholder and customer expectations with minimal risk - sometimes the invisible hand of the market suffices, and other times the firm's own grip is needed on the wheel.

Sources: Economic theories of the firm (Coase: "The Nature of the Firm"), Revista ESPACIOS | Vol. 37 (No. 01) Ano 2016; analysis of vertical integration benefits and costs (What Is Vertical Integration?); McKinsey & Wharton insights on when to integrate (When and when not to vertically integrate | McKinsey), Vertical Integration Works for Apple - But It Won't for Everyone - Knowledge at Wharton; case examples from tech and industrial firms (Netflix Marketing Strategy: Decoding Their Streaming Success - Marstudio).