Are You Avoiding High-Risk, Low-Gain Decisions?

For a company to be great and survive in the long run, it must adopt a risk-conscious culture. This policy defines "concave decisions"—choices with low upside and potentially high, uncertain downside—and provides guidance to avoid exposing the company to catastrophic risks for minimal gain. It applies to all employees and seeks to reinforce prudent decision-making as we continue to grow through acquisitions.

TL;DR Checklist: Is This a Concave Decision?

Use this quick checklist before making key decisions or taking action. If most answers are "Yes," you're likely facing a concave decision and should reconsider or seek alternatives:

Disproportionate Downside? – Is the worst-case outcome much worse than the best-case outcome is good? (Huge potential loss for a small potential gain) (What is Optionality? How Can Optionality Improve My Performance?). For example, "Am I picking up pennies in front of a bulldozer?"—gaining a little if all goes well, but risking a lot if it goes wrong.

Catastrophic or Irreversible? – Could a failure lead to irreversible damage or a catastrophe (e.g. major outage, data loss, legal penalty) while success only gives a minor benefit? If the decision risks the company's survival or reputation for a trivial gain, it's concave. (Never bet the firm for a small reward.)

Probability Blindness? – Are you relying on the low probability of bad outcomes to justify the action? Remember that if an outcome's downside is unacceptable (ruinous), even a low probability is too high (Principles by Ray Dalio). In other words: "Make sure that the probability of the unacceptable (risk of ruin) is nil."

No Skin in the Game? – Would you make the same decision if you personally suffered the downside? If not, be wary. Misaligned incentives (when decision-makers don't bear consequences) often lead to concave risks (Antifragile by Nassim Nicholas Taleb – Summary & Notes). Always imagine you "go down with the ship"—it focuses the mind on truly unacceptable downsides.

Safe Alternatives Ignored? – Have you skipped safer options or incremental tests that cap downside? (E.g. not piloting a change on a small scale first.) If a more convex approach (low downside, high upside) exists, pursue that instead of a high-downside leap.

Gut Check – Any Black Swans? – If an unforeseen "Black Swan" event occurred (something highly unexpected), would this decision blow up disproportionately? Fragile (concave) plans break under volatility (Nassim Nicholas Taleb: To Prevail in an Uncertain World, Get Convex – Articles – Advisor Perspectives). Ask yourself, "If things change suddenly or we're wrong in our assumptions, what's the damage?" If the answer is "devastating," avoid or redesign the action.

Use the above as a personal checklist. When in doubt, pause and escalate the decision to a manager or risk review committee. It's always better to slow down than to charge into a potential disaster.

Supporting Insights and Theory: Antifragility, Asymmetry, and Risk Culture

Understanding the theory behind this policy will help internalize why we avoid concave decisions. Our approach is inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb's concepts of antifragility, along with principles from risk management, decision theory, and behavioral economics:

Convex vs. Concave Payoffs (Taleb's Antifragility)

In Taleb's framework, fragile things have more downside than upside from shocks, which he calls a concave payoff profile. By contrast, antifragile things benefit from volatility—a convex profile where upside outweighs downside. We want to position our decisions and strategies to be convex (or at least robust), never concave. In practice, this means setups where we are harmed much more by an error than we can benefit from a correct call are to be avoided (Lead Time Distributions and Antifragility | Connected Knowledge). Taleb uses the analogy of convexity like a financial option—limited loss if wrong, big gain if right—whereas concave exposures are like "picking up pennies in front of a bulldozer." Our policy institutionalizes this wisdom: seek decisions that gain from uncertainty or at least resist it, and shun those that break under volatility.

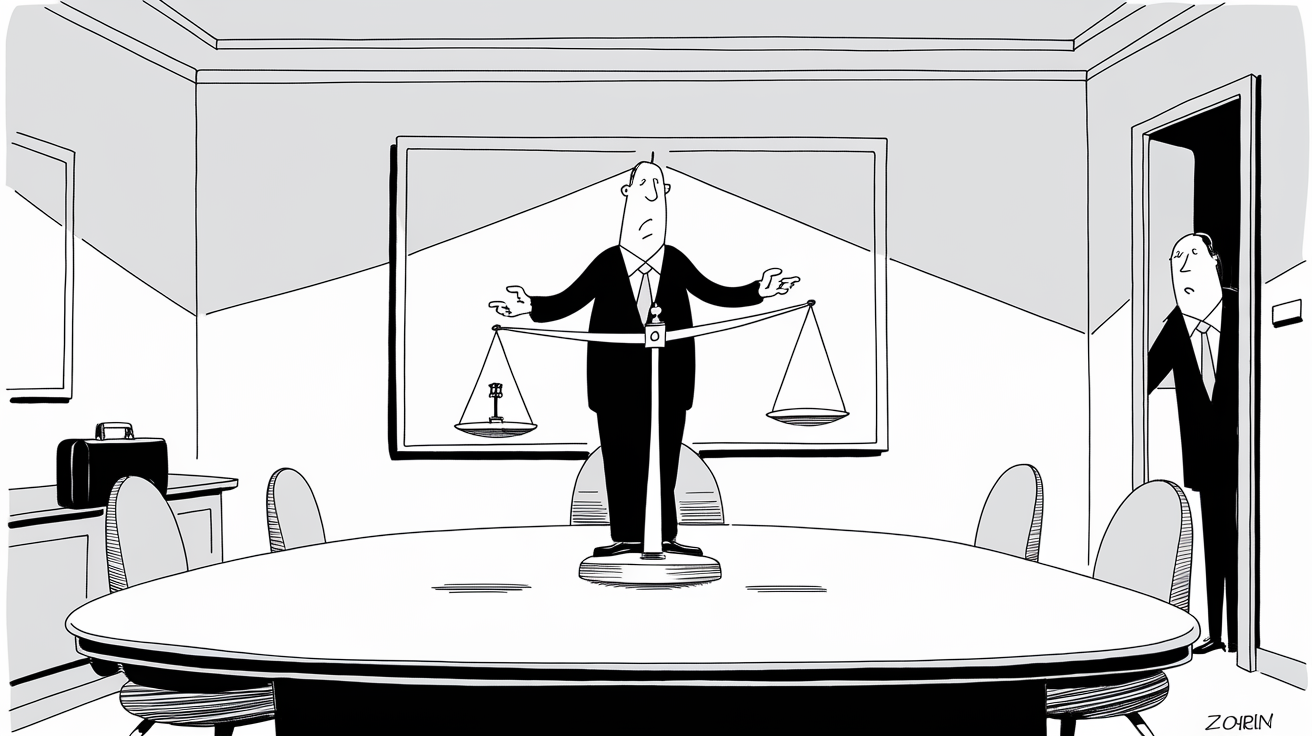

"Skin in the Game" – Accountability and Incentives

Taleb famously notes that the "largest source of fragility" is the absence of skin in the game. When individuals do not personally bear the consequences of their risks, they may take reckless or concave bets. This policy insists on a culture of ownership and accountability: we encourage asking, "If I had to live with the worst outcome, would I still proceed?" Decisions that pass off extreme downside to the company (or others) while offering only minor upside to the initiator are unethical and fragile (Having 'Skin in the Game' – Common Dreams). We remediate this by aligning incentives—major proposals with significant risk must be approved by those who have a stake in long-term outcomes, ensuring no one is playing with asymmetric house money.

"Never Risk Ruin" – Downside Protection as Strategy

Prominent strategists and investors reinforce the idea that avoiding catastrophic downside is priority one. As investor Ray Dalio advises, "Make sure that the probability of the unacceptable (i.e., the risk of ruin) is nil." In practice, this means no initiative or deal should ever carry a plausible chance of bankrupting the company or permanently crippling our business—no matter the supposed upside. The expected value of a gamble is irrelevant if it includes even a tiny probability of ruin, because ruin = game over. We prefer strategies that survive to fight another day. This mindset is echoed in business strategy research as well. In Great by Choice, Jim Collins describes "productive paranoia"—the best leaders continuously ask "What if?" and prepare for worst-case scenarios (Productive Paranoia: Lesson #3 From Jim Collins' Great By Choice | Stephen Blandino). They build buffers and avoid recklessness, knowing that only the mistakes you survive can teach you lessons. We foster a similar paranoia about big downsides: plan for shocks and never assume "it'll never happen to us." By being hyper-aware of what could go wrong, we either steer clear of those risks or mitigate them to acceptable levels.

Asymmetric Upside (Optionality) vs. Asymmetric Downside

We encourage thinking in terms of asymmetry. A good decision often has limited downside and lots of upside (positive asymmetry), while a bad (concave) decision is the opposite. Taleb and others advocate building optionality into ventures—small bets that could pay off big, while losses are contained. For example, developing a prototype or running a low-cost experiment before a full rollout gives us one-sided exposure: if it fails, losses are minor; if it succeeds, we scale the benefits. This is the opposite of throwing all our resources into an untested idea (which is a high downside gamble). We want to maximize opportunities for upside gain while limiting the downside risk at every step (What's The Barbell Strategy? – Definition, Examples, and More — Wealest). Put simply, "clip your downside, protect yourself from extreme harm, and let the upside take care of itself." By institutionalizing this principle, especially in our post-acquisition environment, we steer teams to favor safe-to-fail experiments and iterative progress over big-bang moves that could backfire.

Behavioral Biases and Traps to Avoid

Be aware of common decision-making biases that tempt us into concave decisions. One is the sunk cost fallacy—the tendency to keep investing in a losing proposition because we've already spent so much on it. This often turns a contained loss into a potentially bigger disaster, essentially "digging ourselves into a deeper hole" (How Sunk Cost Fallacy Influences Our Decisions – Asana). Our policy urges cutting losses early rather than throwing good money (or time) after bad.

Another is risk-seeking under loss: psychology research (prospect theory) shows people often take desperate gambles to avoid a sure loss, even if that gamble could lead to a much larger loss (Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk – JSTOR). In a project context, this means a manager might double down on a failing project with an extremely risky overhaul, hoping to win it all back. Such behavior can convert a small failure into a catastrophe. We encourage an alternative approach: admit small failures, learn, and move on.

Additionally, overconfidence bias can make someone underestimate the downside ("I'm sure this risky demo will wow the client, nothing will go wrong")—counter this by deliberately considering worst-case scenarios (a premortem analysis: "What would be the worst thing that could happen here, and can we live with it?"). By being mindful of these biases, employees can catch themselves before they commit to a concave decision on autopilot. A culture that values rational caution over bravado will naturally filter out many concave risks.

In summary, these theories underscore a simple truth: long-term success comes from avoiding ruinous mistakes even more than achieving brilliant wins. By building an antifragile mindset—benefiting from volatility when possible, but always surviving it—we ensure the company's longevity and health through growth and uncertainty.

Illustrative Examples in an Enterprise Software Context

To make this policy concrete, here are a few scenarios that illustrate concave decisions (and preferred alternatives) in our enterprise software environment. Employees at all levels should learn to spot similar patterns in their day-to-day work:

Overpromising to a Customer (Sales/Account Management)

A sales executive, eager to close a deal, considers promising a critical new feature integration to a prospective client by an unrealistic date. Upside: Might help secure one customer's signature this quarter. Downside: If the promise can't be met, we face an angry customer, damage to our reputation, potential legal liabilities, and firefighting to deliver something our product isn't ready for. This is clearly a concave move—a sliver of upside with massive downside if it fails.

Policy in action: Don't commit to deliverables or timelines that our teams haven't vetted. Instead, take a more convex approach: set honest expectations or offer contractual flexibility. It's better to lose a deal than to win it in a way that could blow up later. Before making bold promises, ask "What if we're wrong?" If the answer is "we lose the customer's trust and others hear about it," don't do it.

"Quick Fix" That Risks System Outage (Engineering/Operations)

An engineer notices a minor bug in the customer analytics module just before a big demo. There's a temptation to apply an untested hotfix directly in production. Upside: If it works, the demo goes perfectly and nobody notices the issue—a small relief. Downside: The unvetted fix could have unforeseen side effects, potentially crashing production or corrupting data. That would ruin the demo and impact all customers.

Policy in action: The engineer should avoid rushing in a risky change. They might find a safer workaround or explain it briefly to the client. Our culture does not penalize someone for not taking a wild gamble with production. We prefer boring stability over dramatic fixes when the stakes are asymmetric. As a rule, never deploy a change that hasn't been tested unless the upside far outweighs the risk—and even then, get a second opinion.

Architecture Shortcut With Asymmetric Risk (Engineering/Architecture)

A development team designing a new service considers using a single database instance for both primary and backup to save time. Upside: Slight reduction in complexity and a quicker initial launch. Downside: A single point of failure—if that database goes down, all data and service availability could be lost at once. The potential impact is enormous, far outweighing the small convenience gained.

Policy in action: Implement proper redundancy (e.g., replication, backups in separate zones). Designing for graceful degradation might seem overly cautious during smooth times, but it is essential for resilience under stress. We reward engineers for robustness—building systems that "fail safe" rather than "fail big."

Pushing a Buggy Release to Meet a Deadline (Product/Engineering)

There's pressure to merge an acquired product into our main platform by the end of the quarter, even though the code hasn't fully passed quality checks. Upside: Hitting a deadline, showing quick integration progress. Downside: If the code is buggy or not well integrated, it could cause critical failures, from security vulnerabilities to broken features for existing customers. That fallout could be many times worse than the benefit.

Policy in action: Delay the launch until it's truly ready. Communicate transparently about the reasons (we value quality over arbitrary deadlines). Perhaps release a beta to a small subset of customers first. Leadership should reinforce that missing a date is acceptable, but a major incident is not.

Risky Behavior in Client Interactions (General)

A consultant or support rep in a customer meeting decides to improvise beyond their authority—sharing unconfirmed information or committing to a contract concession without approval. Upside: Temporarily pleasing the client or diffusing tension. Downside: If the promise is wrong or unauthorized, it can break trust or create legal problems. A trivial short-term gain is not worth the major downside.

Policy in action: Stick to the truth and approved parameters in customer interactions, even in tough conversations. If under pressure, don't gamble on a guess or an unvetted commitment. It's better to say "I'll check with our team" than to expose the company to a promise we can't keep.

Bottom line: Across all departments—from engineering decisions and product strategy to sales tactics and operations—always weigh the asymmetry of outcomes. If an action puts us in a position where "if we're wrong, the hit is far worse than any gain if we're right," that's a concave decision and against our policy. One catastrophic misstep can undo years of goodwill. By applying this policy diligently, we ensure no single decision will sink the ship. Instead, we focus on steady, sustainable growth, where upsides are welcomed and downsides are contained.

Employees are encouraged to discuss potential risks openly and use these principles in day-to-day judgment calls. When in doubt, remember: protecting the company from extreme harm is everyone's responsibility. A culture that avoids concave decisions is one that stays robust under stress and keeps improving—turning uncertainties into opportunities while always safeguarding our foundation.