Short-Term Gains or Long-Term Success?

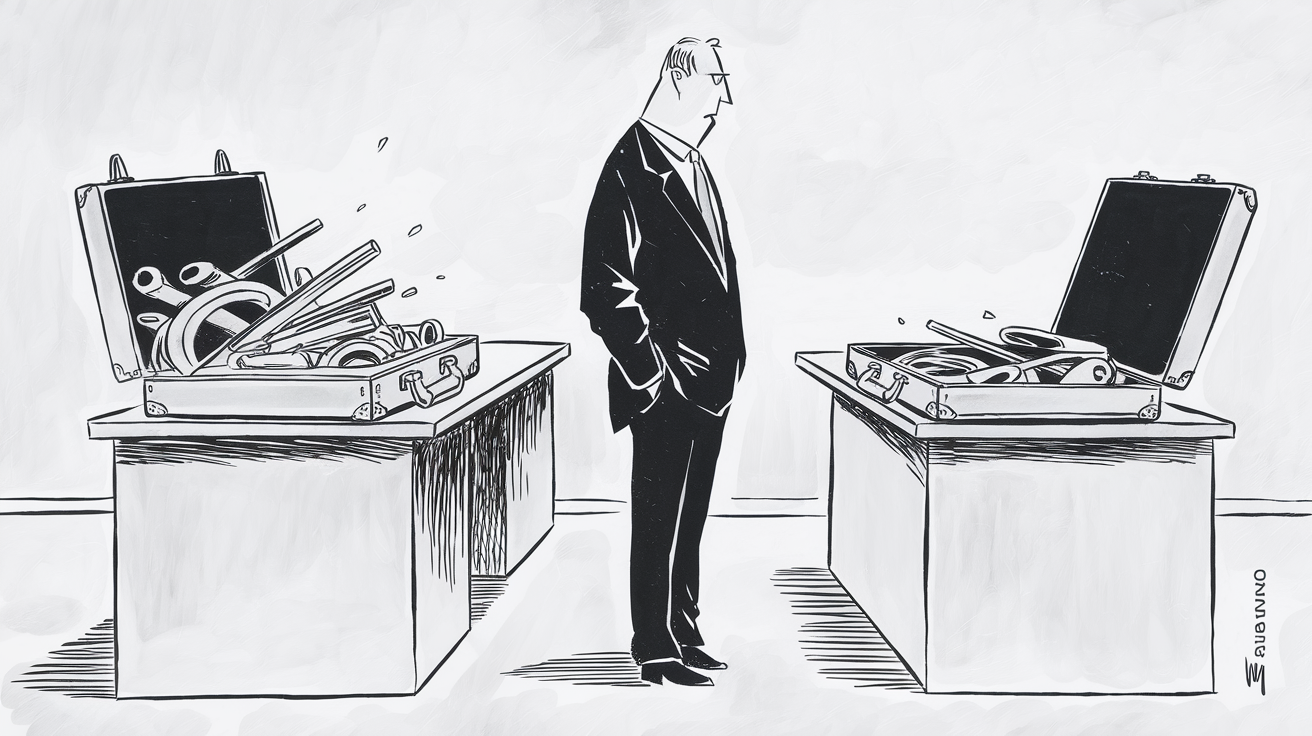

Every organization faces a fundamental strategic tension: how to excel today while securing success for tomorrow. In simple terms, short-term performance thrives on making the most of what you currently have, whereas long-term advantage comes from gaining what others can't easily get. This framework is built on that principle. It is tailored to organizations (from startups to enterprises, though applicable to teams and individuals as well) and balances timeless strategic concepts with actionable guidance. The goal is to provide a clear roadmap for managers to improve immediate results by utilizing current assets better while investing in unique, hard-to-replicate assets for sustainable future gains. We draw on insights from strategic management (for example, exploitation vs. exploration, resource-based theory), organizational behavior (culture, leadership, ambidexterity), and operations (process improvement, asset utilization) to craft a comprehensive approach. Real-world cases – from Toyota's efficiency to Amazon's long-term bets – illustrate how this balance can be achieved in practice. The sections below outline the conceptual foundations, key components of the framework, and examples, concluding with an integrated view on balancing short and long horizons for enduring success.

Conceptual Foundations: Short-Term vs. Long-Term Value Creation

At its core, our framework builds on a duality well-recognized in management theory: exploitation of current resources vs. exploration for new opportunities (Balancing Exploitation and Exploration in Product Strategy). James March (1991) described this as the need for organizations to both exploit existing capabilities and explore new ones to survive and prosper. Similarly, Michael Porter noted that operational effectiveness (doing things well) must be coupled with unique strategy (doing things differently) for sustainable success. Below we define each side of this equation and their theoretical underpinnings:

Short-Term Performance via Current Assets (Exploitation): In the short run, companies win by using what they already possess — their people, capital, facilities, intellectual property, customer relationships — as efficiently and effectively as possible. This corresponds to exploitation in organizational learning theory, which means leveraging existing knowledge, resources, and capabilities to maximize efficiency and profitability. Exploitation focuses on refinement and improvement, yielding immediate gains through cost reduction, productivity, and incremental innovation. In operations terms, this is about eliminating waste and optimizing processes to "boost efficiency, optimize performance, and reap short-term benefits." Techniques like lean manufacturing and Six Sigma exemplify this; indeed the Toyota Production System is famed for "eliminating waste and achieving high efficiency" in production. Organizational behavior research shows that a culture of continuous improvement and performance measurement can unlock latent potential in current assets — for example, engaging employees in problem-solving can raise productivity quickly. The short-term mindset values predictability, stability, and immediate results, often driven by data on current operations. However, exclusive focus here can lead to myopia — over-reliance on the status quo and eventual stagnation or obsolescence.

Long-Term Advantage via Unique Assets (Exploration): Lasting competitive advantage requires assets and capabilities that competitors cannot easily obtain or imitate. This aligns with exploration — "investing in new technologies, strategies, and markets to ensure future growth and adaptation." In strategy theory, this is captured by the resource-based view (RBV) and the concept of "VRIO" resources: to yield sustainable advantage, a resource must be Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and supported by the Organization (VRIO Analysis – Strategic Management). Assets like a powerful brand, proprietary technology, patents/IP, unique talent or know-how, exclusive partnerships, or network effects fall in this category. They function as competitive moats that others struggle to cross. For example, if a firm develops a patent-protected product or a platform with network effects, it gains an edge that is not easily eroded. In practice, exploration means venturing into the unknown — R&D, innovation, strategic acquisitions, entering new markets — with an acceptance of higher risk and delayed payoff. It's the "long game" focus, sacrificing immediate returns for future leadership. Firms pursuing this build unique capabilities or assets over time — what strategy scholars call core competencies or dynamic capabilities (the capacity to continually build and reconfigure assets in changing environments). A classic first-principles example is investing in brand equity: initially intangible, a strong brand "can deliver enhanced competitive advantage, translating into superior market share or margins" over time. Likewise, technology companies often operate at losses initially to acquire a critical mass of users (a unique asset via network effects), knowing that once achieved, the self-reinforcing network can yield monopoly-like advantages. The risk, of course, is that exploration may fail or take too long to pay off; yet without it, an organization eventually loses relevance.

Philosophical Grounding: From a first-principles perspective, this dual approach echoes the age-old balance of "harvesting and sowing." In the present, a firm must harvest efficiently from resources it has (much like maximizing yield from a field), but to ensure future harvests, it must also sow new seeds in fertile ground (develop new assets) even if that means part of today's yield is set aside. Neglect one, and the system fails — only harvesting (short-termism) depletes the soil, and only sowing (long-termism) means no sustenance today. Modern theories use different language — exploitation vs. exploration, efficiency vs. innovation, execution vs. strategy — but all recognize the need for balance. Companies that endure are "ambidextrous organizations" capable of operating in the present while innovating for the future. This framework therefore emphasizes managing the tension: drive exploitation to fuel current performance, and use a portion of that success to fund exploration, thereby building unique assets that secure tomorrow's advantage. In practice, that means concurrently focusing on two horizons — the now and the next.

Framework Overview and Components

To operationalize these ideas, we propose a structured framework with two parallel tracks and a bridging mechanism. Track 1 (Short-Term) focuses on diagnosing and maximizing the utilization of current assets for immediate performance improvements. Track 2 (Long-Term) focuses on identifying, acquiring or developing unique assets that will form the basis of future competitive advantage. A bridging mechanism ensures that the two tracks support rather than undermine each other — aligning short-term wins with long-term strategic intent. Below, we break down the framework into key components, each with conceptual rationale and actionable steps:

1. Audit Current Assets and Capabilities (Know What You Have)

Any strategy begins with understanding the status quo. Inventory the organization's current assets, capabilities, and resources. This includes tangible assets (factories, equipment, cash, etc.) and intangible assets like human capital (employee skills, knowledge), intellectual property (patents, proprietary tech), customer assets (existing customer base, data, loyalty), brand reputation, and organizational processes. The goal is to map out what the company can already leverage. Tools like a SWOT analysis or a VRIO analysis are useful here. For example, an internal audit might reveal that a firm has a highly skilled engineering team and several under-utilized patents — valuable assets that could yield more short-term output. It might also identify slack or underperforming assets (for example, idle equipment or excess inventory). Key questions: What assets are currently underutilized? What capabilities do we excel at? What customer relationships or data do we possess? What intellectual property or expertise do we own that isn't fully monetized? This audit sets the stage for both optimizing today's operations and for spotting which unique assets could be built upon for tomorrow.

2. Short-Term Performance Improvement Plan (Exploit Current Assets)

With a clear picture of current assets, the next step is systematically improving efficiency and output using those assets. This component is about exploitation — turning slack into throughput and leveraging strengths to their fullest. Actionable steps include:

Optimize Operations and Processes: Apply lean management and continuous improvement to eliminate waste in production or service delivery. By refining processes, organizations can do more with the same resources. For instance, Toyota's lean practices enable "more production with a smaller workforce," essentially increasing output per asset. Techniques like Six Sigma, process re-engineering, and agile workflows fall here. Metrics: track efficiency KPIs (cycle time, defect rates, asset utilization rates). Southwest Airlines famously achieved 20–25 minute airplane turnarounds, far faster than rivals' 45+ minutes, by organizing gate crews for speed and efficiency. This high asset utilization (planes spending more time in the air) allowed Southwest to serve the same demand with fewer planes — a direct short-term performance boost (more flights per day, lower cost per seat) achieved by exploiting current assets. Example: In its early years with only four aircraft, Southwest challenged employees to turn planes around in under 30 minutes; through continuous improvement experiments, they hit a 22-minute turnaround — enabling them to maintain schedules with 25% fewer planes. The payoff was immediate in cost savings and revenue per plane.

Maximize Human Capital Productivity: Current employees are a key asset. Short-term, a firm can invest in training programs to quickly upgrade skills needed for existing operations, reorganize teams to better align talent with tasks, and boost motivation through incentives and culture. Research shows engaged, empowered employees contribute more discretionary effort. Tactics such as setting clear short-term performance goals, offering quick feedback loops, and recognizing achievements can unlock greater output from the same workforce. For example, a consulting firm might create cross-functional "tiger teams" to solve client issues faster using expertise already in-house, or a software company might repurpose some developers to troubleshoot backlog bugs, improving product performance without new hires. A culture of ownership and excellence can dramatically improve how current human assets perform in the short run.

Exploit Existing Customer Base and Data: Customers and their data are assets that can yield quick wins. In the short term, firms should leverage customer relationships to drive repeat sales or upsell (for example, targeted marketing campaigns to existing clients, loyalty programs) rather than costly new customer acquisition. They can also use customer data and feedback (a byproduct asset of operations) to refine offerings or personalize services, thus increasing immediate sales conversion. For example, Amazon's recommendation engine uses the company's vast customer purchase data (an asset) to drive additional purchases in the short term. Many companies underutilize their customer databases; a focused effort to analyze and act on this data (via CRM systems, tailored promotions) can rapidly boost revenue using "assets you already have — your customers' attention and information."

Leverage Intellectual Property and Knowledge: If the audit identified patents, proprietary software, or expertise that isn't fully utilized, find quick ways to monetize them. This could mean licensing a dormant patent to another firm for royalty income, repackaging existing content or research into a new product, or deploying an internal tool company-wide to improve productivity. For instance, if a biotech firm has research findings that are not in its core product line, it might license those to partners, generating short-term revenue from an existing intellectual asset. Likewise, internal process innovations could be codified and sold as a service (as IBM did by turning its IT operations know-how into a consulting offering). Key principle: squeeze more value from each asset on the balance sheet. This improves asset turnover and immediate financial performance. As one study notes, higher asset utilization generally correlates with higher short-term profitability, all else equal. Management should set targets to improve utilization ratios (like the sales-to-assets ratio or working capital turnover) and track progress.

Financial and Operational Discipline: Ensure that short-term operational decisions optimize resource use. This can include tight working capital management (efficient use of cash, inventory, receivables) so that current assets generate maximum liquidity and returns. A company with large amounts of capital tied up in inventory can free cash by better demand forecasting, improving short-term financial performance and enabling investment elsewhere. Adopting supply chain finance or just-in-time inventory can improve working capital utilization. Similarly, rationalizing product lines or SKUs to concentrate on the most profitable ones can yield quick margin improvements using existing production assets. In essence, ruthless prioritization of current activities — focusing on what yields the most value now — is key. Example: When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, he slashed the product lineup from dozens to just four main products, allowing the company to concentrate its hardware, engineering, and marketing assets on the few winners. This drastic focus improved short-term clarity and efficiency, laying the groundwork for Apple's comeback.

By executing such initiatives, organizations can often see rapid performance gains — higher productivity, lower costs, improved cash flow — without acquiring new resources, purely by fully leveraging current ones. This generates not only better short-term results but also capacity (financial and organizational) to invest in the long term. It's important, however, that these efficiency moves do not undermine future capability — for instance, avoid cost cuts that demoralize staff or starve R&D. The guiding philosophy should be "improve, but don't impair." Done right, short-term exploitation becomes a virtuous cycle, freeing up resources (profits, manpower, attention) that can be funneled into long-term development. As summarized by one LinkedIn strategy piece, short-term goals are the lifeblood that keep a company competitive and afloat in the present, but an overemphasis on them can erode long-term health if not checked. Hence the need for the next part of the framework: balancing with long-term moves.

3. Long-Term Asset Investment Plan (Explore and Acquire Unique Assets)

In parallel with short-term optimization, companies must devote energy to building the future. This component involves identifying which unique or hard-to-replicate assets will be critical for sustainable advantage and formulating a plan to acquire or develop them. It is a deliberate shift from harvesting to planting. Key steps include:

Vision of Future Competitive Advantage: Leadership should articulate a clear vision of where the long-term wins will come from. Ask: "What will set us apart in 5, 10, 20 years? What assets or capabilities will we need to win, that competitors will find difficult to match?" This could be technological leadership, brand dominance, an unrivaled distribution network, a broad ecosystem or platform, proprietary data, or a combination. For example, a pharma company might identify its long-term advantage will hinge on having a robust pipeline of patent-protected drugs (IP assets), whereas a platform tech company might see that achieving a critical mass of users (network asset) or an AI algorithm trained on unique data will secure its future. This vision should be informed by strategic foresight (for example, scenario planning, trend analysis) and by the organization's purpose.

Identify Gaps and Opportunities: Once the desired future assets are known, perform a gap analysis between what the company currently has (from the audit in Step 1) and what it needs to develop or acquire. For instance, if a retailer sees long-term advantage in customer loyalty and brand, do they currently have strong brand equity? If not, brand-building is a gap. If a manufacturing firm bets on a proprietary technology, do they have the R&D capability or should they acquire a startup with the tech? This step often leverages strategic management tools like core competency analysis and an understanding of industry evolution. It also relates to the concept of dynamic capabilities: the firm's ability to adapt by building new competencies.

Invest in Asset Acquisition/Development: With targets set, the organization must take action to acquire or create those unique assets. This often requires significant long-term investment — in R&D, talent, marketing, partnerships, or acquisitions — which may not pay off immediately. Top management must allocate resources boldly toward these strategic priorities, even if it means near-term earnings pressure. McKinsey research supports this, finding that companies that proactively reallocate resources toward future growth opportunities tend to outperform those that stick to incremental, status-quo spending. This could mean funding a skunkworks innovation lab, increasing the R&D budget as a percent of sales, or buying companies that possess the desired assets (for example, acquiring a firm for its patented technology or its user base). Examples of actions:

Innovation and R&D: Ramp up research in relevant areas, experiment with new product lines, or pioneer a new business model. Google's famous "20% time" policy let employees explore ideas outside their core job, leading to products like Gmail. Amazon consistently invested heavily in R&D (far above retail industry norms), which yielded unique assets like its recommendation engine and AWS cloud platform.

Capability-Building Programs: Develop unique human capital through hiring and training. If long-term advantage requires AI expertise, start building an AI center of excellence, train existing staff or recruit top scientists. Over time, the collective knowledge becomes an inimitable asset.

Brand Building: Invest in marketing, customer experience, and quality to strengthen brand equity. Brand is an intangible asset that accumulates with consistent effort — and a strong brand "is among the most valuable assets a company owns," often not reflected on balance sheets. For example, Coca-Cola's decades of marketing and distribution have built one of the world's most imitable brands, allowing it to maintain premium pricing and customer loyalty. Building brand may involve entering new markets to make the brand global, associating the brand with social causes, or improving product quality relentlessly so that the brand stands for excellence.

Platforms and Network Effects: In the digital era, fostering network effects can be a powerful long-term strategy. This might mean launching a platform where third-party users or partners add value (for example, a marketplace, a developer ecosystem). Early on, this requires subsidizing growth to reach critical mass. But once a network effect kicks in, it becomes a self-reinforcing asset.

Data and Intellectual Property: In many industries, proprietary data is emerging as a key asset. Companies should actively accumulate and protect data assets — through encouraging user engagement, IoT sensors, etc. — and develop unique algorithms or patents from this data. A pharma company's patent portfolio or a tech firm's library of algorithms can be a long-term moat. However, note that if data or IP can be easily copied, it won't confer long-term advantage — so invest in those that can be made proprietary.

Alliances and Ecosystem: Sometimes the unique asset is not owned but accessed. A company can secure long-term advantage via exclusive partnerships or contracts that competitors can't get. For example, a defense contractor might lock in a 10-year government contract, or a tech firm might form an alliance for exclusive rights to a new technology.

Adopt a Portfolio Approach (Horizon Planning): It often helps to use a strategic portfolio mindset, such as McKinsey's Three Horizons framework, to balance short- and long-term initiatives. Horizon 1 projects exploit current capabilities for near-term returns; Horizon 2 initiatives nurture emerging opportunities; Horizon 3 explores nascent ideas for the future. For example, a company might allocate 70% of its innovation budget to improving existing products, 20% to adjacencies or new market expansions, and 10% to blue-sky research. This ensures continuous long-term development without jeopardizing short-term core business.

Patience and Milestones: Long-term asset building requires patience and different metrics. Managers should set milestones to track progress on these initiatives (for example, R&D milestones, brand awareness scores, user growth numbers) rather than near-term ROI. It's crucial to communicate to stakeholders that these investments are intended to pay off over a longer horizon. As Jeff Bezos wrote in Amazon's 1997 shareholder letter, "We will continue to make investment decisions in light of long-term market leadership considerations rather than short-term profitability considerations or short-term Wall Street reactions." That philosophy allowed Amazon to pour cash into distribution infrastructure, technology, and customer base expansion — building the unique assets (scale, brand, loyal customer base, AWS technology) that eventually made it one of the world's most valuable companies. Over time, hitting milestones provides proof points to justify the strategy and inform any course-corrections.

In summary, this long-term track is about deliberately building moats: assets that are valuable, scarce, and hard for others to copy. While the specific nature of the asset will vary by company and industry, the common thread is uniqueness. Through sustained investment and strategic focus, the firm accumulates advantages that competitors either cannot obtain at all or can only do so at great cost or time lag. These unique assets form the basis of sustained superior performance. The next section will provide concrete examples of how companies have executed both tracks effectively.

Illustrative Examples and Case Studies

To make the framework more tangible, let's look at a few real-world examples where businesses have excelled at either short-term asset utilization, long-term asset acquisition, or ideally both. These cases span different industries and asset types, illustrating the versatility of the framework:

Toyota (Short-Term Excellence Feeding Long-Term Strength): Toyota Motor Corporation provides a classic example of balancing immediate efficiency with unique capability development. In the short term, Toyota's implementation of the Toyota Production System (TPS) exemplifies exploitation of current assets. TPS relentlessly cuts waste and improves how every asset (workers, machines, floor space) is used, yielding superior short-term productivity and quality. It's often noted that TPS enables "more production with less resources" — a direct short-term competitive edge. But Toyota didn't stop at operational efficiency; it reinvested in developing unique long-term assets. One such asset was its expertise in hybrid engine technology. In the 1990s, Toyota poured R&D into hybrid drivetrains when others were not, resulting in the launch of the Prius in 1997. The Prius's success gave Toyota a brand reputation for environmental innovation and a patent portfolio in hybrids that competitors struggled to match for years. Toyota's hybrid leadership became a hard-to-replicate asset. Thus, Toyota leveraged short-term efficiency gains (which boosted profits) to fund pioneering work that secured a long-term advantage in hybrids.

Southwest Airlines (Maximizing Current Assets): Southwest in its early decades focused heavily on exploiting what it had to achieve cost leadership in the airline industry. Its fast turnaround operations meant higher plane utilization. Southwest also had a unique approach to human assets — creating a culture of empowered, spirited employees who took pride in efficiency. This culture (an intangible asset) meant that front-line staff were constantly finding ways to keep costs low and planes on time. In one instance, Southwest's ground crew managed to cut plane servicing down to 22 minutes to keep the schedule with fewer aircraft. These short-term tactics allowed Southwest to consistently have the lowest costs in the industry, which it translated into low fares and rapid market share gains. Regarding long-term assets, one could argue Southwest's culture and brand became unique assets. The company's fun-and-friendly image, combined with reliable low-cost service, created a loyal customer base that legacy carriers found hard to steal. That culture kept employees engaged and productivity high (feeding short-term performance) and also served as a moat against rivals.

Apple Inc. (Designing Unique Assets for Long Term, Leveraging Existing Strengths): Apple offers a compelling study in building unique assets like brand and ecosystem, while also exploiting current capabilities. In the late 1990s, when Steve Jobs returned, Apple was nearly bankrupt. Jobs first executed short-term moves to simplify and optimize — trimming the product line to focus on the iMac, cutting costs, and utilizing Apple's remaining talent on a few key projects. With the company stabilized, Apple then swung to long-term asset building. It invested heavily in design and user experience — eventually leading to the iPod, iPhone, and related software ecosystems. Each of these involved acquiring or developing unique assets: the iPod was bolstered by Apple's proprietary iTunes software and music licensing deals, and the iPhone was backed by numerous patents, a custom chip design capability, and the revolutionary App Store. Over the 2000s, Apple's brand transformed into one of the most powerful in the world — a meaning-based asset tied to innovation and quality. Consumers became willing to pay premium prices, a classic sign of strong brand equity. Additionally, Apple's ecosystem lock-in (iOS, App Store, iCloud connectivity) became a unique strategic asset — once customers invested in Apple's world, switching costs were high. By 2025, these assets (brand loyalty, ecosystem integration, design expertise, proprietary chips) form an inimitable competitive moat. Apple illustrates the virtuous cycle: short-term profits from current products are reinvested into design, software, silicon, and brand-building — yielding ever more differentiated future products.

Amazon (Sacrificing Short-Term Profits for Long-Term Assets — and Then Reaping Both): Perhaps no modern company is cited more for long-term thinking than Amazon. Jeff Bezos from the outset instilled a philosophy of foregoing short-term earnings in order to invest in customer base, technology, and scale for the long term. In practice, Amazon exploited some current assets masterfully. For example, in the early 2000s, it used its existing e-commerce platform and distribution centers not only to sell books but quickly added new product categories. It also mined its customer purchase data to create a recommendation engine that immediately boosted cross-sales. However, Amazon was more than willing to let the short-term profit numbers suffer because it funneled gross profits into building unique assets: the Prime membership program, AWS, a vast logistics network, and a brand known for customer obsession. These assets were costly and took years to fully mature, but when they did, Amazon gained near-unassailable advantages. AWS, for instance, started as an internal asset — excess server capacity and IT expertise — which Amazon realized it could offer as a service. Investing in it long-term gave Amazon a multi-year lead in cloud infrastructure, which today provides over half of the company's operating profits. Similarly, Prime was a long-term play: Amazon invested in faster shipping and content to make Prime invaluable; short-term it incurred huge costs, but long-term it locked in tens of millions of subscribers. The result: Amazon achieved both unprecedented scale (short-term revenue performance) and entrenched unique assets (brand, data, logistics, AWS, Prime ecosystem).

Netflix (Evolving Assets From Short-Term to Long-Term): Netflix transitioned its asset base to maintain competitive advantage. In its DVD-by-mail era, Netflix's key assets were its distribution network and its recommendation algorithm. These yielded strong short-term performance in the form of subscriber growth and low churn. However, Reed Hastings anticipated that the long-term advantage would come from streaming technology and exclusive content — assets quite different from the DVD era. Netflix made the difficult decision to invest early in streaming delivery and later in original content production, a capability it never had before. Early investments in original shows like House of Cards were essentially bets on creating a content library and brand that would differentiate Netflix in the long run. These moves were costly — Netflix famously took on debt to finance content — but they paid off by making Netflix a globally recognized entertainment brand with a content catalog that is a unique asset. Meanwhile, Netflix did not neglect exploiting current assets: its recommendation engine and user data analysis continued to improve to personalize experiences, keeping short-term engagement high. The Netflix story underscores the importance of pivoting asset strategies: short-term excellence in one era (DVD distribution) must be reinvested into building the assets for the next era (streaming tech, content IP).

Facebook (Meta) (Network Effects as Long-Term Asset): Facebook's initial short-term success came from rapid user growth in a simple social networking site. It recognized that its enduring value would lie in massive network effects and the data generated by that network. Thus, it prioritized user growth over immediate monetization. Once the user network reached critical mass, it became a unique asset that no new entrant could easily replicate. Facebook then turned on monetization via targeted advertising, using the treasure trove of personal data gathered over time. It also acquired potential competitive threats (Instagram, WhatsApp) to secure long-term dominance in social media attention and data. In terms of exploitation, Facebook continuously refines its algorithms and ad platform to maximize revenue from its existing user base in the short run. But it funnels a chunk of profits into long-term plays like virtual reality, aiming to build unique assets in a future computing platform.

A common theme is that the most successful companies manage to do both exploitation and exploration well, leveraging operational excellence to fund the development of unique assets. Each example also illustrates the consequences of imbalance: if Netflix hadn't invested in streaming, or Amazon hadn't built AWS, their initial assets would eventually lose value. Conversely, if Toyota or Southwest had ignored operational efficiency, they might not have had the profits or reputation to invest in future assets. The table below summarizes key differences between the short-term (current asset utilization) approach and the long-term (unique asset acquisition) approach, along with how a balanced strategy addresses both:

| Dimension | Short-Term Focus – Exploit Current Assets (Performance Now) | Long-Term Focus – Explore/Acquire Unique Assets (Future Advantage) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Maximize immediate performance: efficiency, output, profit from existing resources. | Build sustainable competitive advantage: differentiation, innovation, "moats." |

| Nature of Activities | Refinement of what is known: process improvement, cost reduction, incremental innovation, expansion of current offerings. E.g. streamline operations, improve asset turnover, upsell existing customers. |

Exploration of new possibilities: R&D, capability development, venturing into new markets/technologies. E.g. design new products, invest in brand, acquire new tech or talent. |

| Asset Emphasis | Tangible & existing intangibles: factories, workforce, current IP, customer base, data on hand, cash flows. Utilize these fully. Metrics: operational KPIs (cost per unit, ROI on assets, productivity), short-term financials. |

Intangible & difficult-to-copy assets: brand equity, patented tech, proprietary data, network size, unique culture, strategic alliances. Grow or obtain these. Metrics: innovation metrics, customer lifetime value, brand awareness, user engagement, other leading indicators. |

| Time Horizon | Immediate to ~1 year. Quick wins and continuous improvements that show results within reporting periods. | Multi-year to decade. Investments with payback often beyond 1–3 years; focus on the "long game" where payoff compounds over time. |

| Risk Profile | Generally lower risk & uncertainty: based on established methods and markets, so outcomes more predictable. Risk of complacency if environment shifts. | Higher risk & uncertainty: involves untested ideas, emerging tech or markets; some bets will fail. Market/technology risk is high, but not investing is risky long-term. |

| Organizational Approach | Often aligns with tight budgets, clear hierarchies for efficiency, KPIs tied to near-term results. Favored by cultures valuing discipline and consistency. Uses existing org structure. | May require separate innovation teams or skunkworks to avoid being stifled. Encourages a culture of experimentation and tolerance for failure. Leadership must champion a vision and protect long-term projects from short-term pressures. |

| Examples | Toyota's lean production (best-in-class efficiency); Southwest's high aircraft utilization. These yield immediate cost or revenue benefits. | Apple building its iOS ecosystem and brand (now a moat); Pfizer investing in biotech R&D leading to a new drug patent; Amazon building AWS platform. |

| Failure Mode (if isolated) | Short-termism: Myopic focus can lead to underinvestment in future, causing stagnation. | Futurism without execution: Over-focus on long term can strain finances and organizational focus. |

| Balanced Strategy | Achieve efficiencies to generate resources and capabilities that feed into long-term investments. Maintain excellence in core business to fund exploration. | Simultaneously, invest part of those resources in creating the differentiators of tomorrow. Accept lower short-term margins as "investment mode" when needed. |

Balancing the Two Horizons: Integration and Execution

Successfully implementing this framework means managing the dynamic tension between short-term and long-term priorities on an ongoing basis. It is not a one-time division of tasks, but a continual balancing act. Here we outline strategies for integration, drawn from research on organizational ambidexterity and best practices in strategic execution:

Structural Ambidexterity: One proven method is to organize for both modes. This could mean separate teams or divisions for exploitative vs. explorative initiatives. For example, a core operations team focuses on efficiency and meeting this year's targets, while an R&D or new ventures group focuses on future opportunities. Each group can have its own processes, metrics, and culture suited to its task. Both ultimately report to top management to ensure alignment.

Cultural Ambidexterity (Contextual Ambidexterity): In addition to or instead of structural separation, organizations can foster a culture that supports both discipline and innovation. This is sometimes called contextual ambidexterity — where the same people and units make judgments on how to divide their time between exploit and explore. To achieve this, leadership must communicate the importance of both goals. They should reward employees not just for hitting short-term numbers but also for contributing to longer-term improvements. Creating cross-functional teams for special projects can help diffuse an innovation mindset into the operational core. Companies like 3M famously allow employees to spend a portion of time on exploratory work — this cultural norm yielded products like Post-it notes. Culturally ambidextrous firms instill values of efficiency and creativity.

Leadership and Governance: Strong leadership is the linchpin of balancing acts. Leaders must set a clear strategic intent that encompasses both short and long horizons, so that everyone understands the dual goals. It's the leader's role to prevent extreme short-termism (like sacrificing R&D for this quarter's profit) and also to rein in impractical long-term projects that aren't bearing fruit. Governance mechanisms can also enforce balance: for instance, a board can set KPIs that include innovation metrics, not just quarterly EPS, thus holding the CEO accountable for future readiness. Some companies create a strategy committee or use the annual planning process to ensure a certain percentage of resources go to strategic initiatives beyond the core. Stage-gate processes for R&D provide disciplined check-ins for long-term projects, ensuring learning and alignment.

Linking Short-Term and Long-Term Goals: The framework works best when short-term improvements advance the long-term agenda, rather than being separate or conflicting. This requires smart alignment of goals. For example, if a long-term goal is to build a superb brand, short-term customer service metrics can be tied to that. If long-term success needs a new technology, short-term goals might include pilot testing that technology on a small scale — yielding immediate feedback and skills while progressing toward the big goal. The Balanced Scorecard approach is useful here: it encourages setting objectives across financial (short-term) and learning/innovation (long-term) perspectives, and mapping how the short-term achievements lead to long-term outcomes.

Financial Management – Funding the Future: From a financial standpoint, firms should explicitly allocate a portion of current cash flows to long-term investments before distributing profits or bonuses. Treat it as paying yourself first — a "strategic investment fund" that is sacrosanct. This counters the tendency to use all surplus for short-term shareholder returns. Another tool is scenario analysis: ensure the firm can survive short-term pressures while those investments are in progress. Maintain a "strategic reserve" of cash or borrowing capacity to sustain long-term projects even if a downturn hits the core business. It's also wise to measure long-term value creation explicitly, using methods like Economic Value Added (EVA) or NPV calculations for big projects.

Monitoring and Adaptation: Balance is not a static 50/50; it may tilt over time. Early in a company's life, more emphasis might be on long-term asset building, then later shift to harvesting, or vice versa. Management needs to constantly monitor both performance and capability metrics. If short-term performance is lagging far behind, maybe over-exploration is an issue. If the pipeline of new products is dry, it's a signal that exploitation has taken over and exploration needs a boost. The framework is iterative: periodically review the mix of exploitation vs. exploration and adjust. Strategy off-sites can dedicate sessions to "running the business" and "changing the business" to ensure both get attention. A simple mantra like "Execute today, invent tomorrow" can keep the message clear.

Finally, there's a psychological aspect: short-term wins are more immediately gratifying, whereas long-term wins require imagination and faith. Good leaders celebrate interim milestones of long-term projects to create a sense of progress and tie them to the company's purpose to keep motivation high. Likewise, they frame efficiency drives as ways to empower innovation: "If we save X now, we can invest it in our new venture — so let's do this!"

Conclusion

In conclusion, the proposed strategic framework emphasizes a dual path to business success: (1) relentlessly leverage your current assets to drive short-term performance, and (2) persistently invest in unique, hard-to-copy assets to secure long-term competitive advantage. We rooted this framework in established theory — from the exploitation/exploration trade-off to resource-based advantages — and demonstrated its validity with examples of companies that achieved remarkable results by balancing both elements.

The core philosophy is simple: "Strengthen today and shape tomorrow." In practice, that means creating an organization that can run efficient operations, delight current customers, and hit this quarter's targets while also exploring new ideas, nurturing new capabilities, and building for the future. The framework is not about choosing one over the other, but about sequencing and aligning: using short-term successes to fuel long-term bets, and letting long-term vision guide what short-term moves to make. Businesses that master this dynamic can enjoy the best of both worlds — robust performance now and a growing competitive edge over time.

From a first-principles standpoint, a business is a system that must concurrently optimize for present viability and future viability. Just as a farmer saves seed from this harvest to plant the next, or as a champion sports team both plays to win each game and grooms young talent for upcoming seasons, a company must deliver results today and build capacity for tomorrow. This framework offers a structured approach to doing so, ensuring that immediate gains don't come at the expense of future potential, and future investments are continually nourished by present capabilities.

To implement this framework, leaders should assess their organizations on both dimensions regularly: Are we fully utilizing what we have? Are we developing what we need? The strategies and tools discussed — from lean operations to ambidextrous structures — can then be employed to address any gaps. By maintaining this balance, organizations can navigate competitive environments that demand efficiency and innovation.

In summary, the path to enduring success lies in exploiting strengths and exploring opportunities in tandem. A short-term vs. long-term mindset is a false dichotomy — world-class companies do not choose, they integrate. They excel at operational performance and strategic innovation. They sweat their assets to fund their dreams. They deliver quarterly results and visionary leaps. With the framework and examples above, managers can formulate strategies that achieve this balance, driving superior results today while systematically building the moats and mountains that will protect and elevate the business in the years ahead.

Sources

- Dotwork – Balancing Exploitation and Exploration: definition of exploitation (efficiency, immediate gains) vs. exploration (innovation, long-term growth).

- Barney’s VRIO Framework – criteria for sustained competitive advantage (valuable, rare, inimitable resources).

- EverEdge (Brand Valuation article) – on brand as a competitive asset and strong brands enhancing market share/margins.

- Nasdaq/SeekingAlpha – definition of network effect moats and tendency toward natural monopoly.

- Toyota Europe – explanation of Toyota Production System as a lean system eliminating waste.

- Gray (Jeffrey Liker on Southwest) – description of Southwest’s core activities: high aircraft utilization enabled by lean, productive ground crews, yielding low costs.

- LinkedIn (Emergent Africa) – on short-term vs. long-term goals.

- McKinsey – importance of shifting resources to growth opportunities and not sticking to incremental status quo.

- Amazon Shareholder Letter 1997 (Bezos) – explicit commitment to long-term market leadership over short-term profitability.

- HBS Online – brand is a "meaning-based asset."

- London Business School (LBS) – concept of organizational ambidexterity, need to balance exploration and exploitation.

- McKinsey (short-termism) – study showing long-term oriented companies outperform, cautioning against obsession with short-term earnings.